What Education Can Learn From Zig Engelmann

Stop debating pedagogy, start analyzing content

A Problem

I noticed last week that some of my students were mixing up multiplication and subtraction. The problems 2(-5) and 2 - (5) look very similar. Which is multiplication? Which is subtraction? Why? As they get more complicated, with more negatives and more parentheses, it’s easy to get careless and confuse one for the other.

How can I help students understand the difference and avoid this mistake?

Every teacher faces questions like this. Often the solutions feel haphazard. Maybe I find a good approach for this lesson, but next week I have a new puzzle to figure out.

Enter Zig Engelmann

Siegfried (Zig) Engelmann was the lead author of the Direct Instruction curriculum programs.1 The first thing to understand about Engelmann is that he was absolutely obsessed with analyzing the content that we ask students to learn.

To Engelmann, there was no one ideal, content-agnostic way to teach. There was no default lesson plan, no structure that would work for every single piece of content. But he also didn’t try to design each lesson from scratch. His goal was to analyze the content to be taught, and find regularities within that content that led to specific teaching strategies.

Let’s return to helping students tell the difference between multiplication and subtraction.

Engelmann would call this a categorical concept. Categorical means we’re putting things into categories, in this case the categories of multiplication and subtraction. To teach a categorical concept, Engelmann used sequences of examples and non-examples.

So I put together this sequence of examples to help students understand the difference:

This is subtraction:

This is multiplication:

This is multiplication:

This is multiplication:

This is subtraction:

I wrote the examples one by one in a table on the board. Then I asked students to do a quick think and turn and talk about the difference between the two. Next I asked a few check-for-understanding questions on mini whiteboards. I noted a few students still making mistakes and checked in with them individually as we did some paper-and-pencil practice subtracting and multiplying integers. This worked pretty well!

Engelmann didn’t just have the idea to teach with examples and non-examples. He was careful about how those examples are sequenced. When shifting between examples and non-examples, the goal is to change as little as possible so students pay attention to the key differences distinguishing the categories. When giving multiple positive examples in a row, the examples should be as different as possible to help students see the breadth of examples that can illustrate a concept. He also emphasized economy of language: Direct Instruction avoids wordy explanations in favor of well-sequenced examples whenever possible.

Engelmann’s technique for teaching categorical concepts is only one of the ideas that came out of his analysis of content. He also sequenced concepts very carefully, separating concepts that look similar but are different. The introductions of the letters b and d are separated by a number of lessons in the Direct Instruction early reading program because young students often confuse those letters. The two different interpretations of subtraction — taking away (how you likely solve 15 - 2), and finding the difference between (how you likely solve 15 - 13) — are separated as well, rather than being taught one immediately after the other.

Another example is breaking skills down into small pieces, while also ensuring those pieces are meaningful units on their own. A good example is Engelmann’s analysis of word problems in math. Many curricula present word problems as a loose collection of stories with numbers in them and emphasize generic strategies like circling and underlining key information. Engelmann analyzed the different types of word problems and taught students to analyze the specific relationships. For instance, one type of word problem is “combine” problems, where two parts are combined to make a whole. Combine problems can involve either addition or subtraction (addition if you are finding the total after combining, subtraction if you are finding one of the parts to be combined). Engelmann’s goal was to isolate this particular type of word problem, help students understand how to solve variations on combine problems, and then move on to a different type of word problem (for instance, a “change” problem where an amount changes).

The depth here is hard to capture concisely. Engelmann didn’t invent a new strategy for every single lesson he designed, but he also didn’t use the same structure for every single lesson. He developed a collection of strategies based on an analysis of the content to be learned, and with that collection of strategies you can teach more or less anything.

Engelmann Was Relentlessly Empirical

What I just described is only a tiny slice of what Engelmann would do to analyze content and figure out the best ways to teach it. Those ideas were published in the book Theory of Instruction, cowritten with Doug Carnine.2 The book is a deep dive into all of the details of teaching different types of content, with chapters on things like “comparative single-dimension concepts.” Theory of Instruction was published in 1982, while the Direct Instruction programs were designed in the mid-1960s and first published in 1968. What took so long?

The ideas in Theory of Instruction are better thought of as the result of designing the Direct Instruction programs, rather than something that existed before they were designed. Engelmann was relentlessly empirical in his process of curriculum design, and Theory of Instruction grew out of that empiricism.

To understand this process, you first have to understand how students were placed into a Direct Instruction program. In a typical school, all of the second grade students start with the first lesson of the second grade curriculum, march through the curriculum, and move on to the third grade curriculum when they reach third grade. Engelmann’s programs were different. Each program begins with a placement test designed to figure out what students already know. Then, students are placed into the program based on that placement test, rather than by their age or grade level. Imagine an elementary school (all of Engelmann’s first programs were for elementary students). One group of students would begin with the equivalent of the first lesson of the second grade curriculum, but it would include some second grade students, some first grade students who were a bit ahead, and some third grade students who were a bit behind. There would also be a group of students who would start with the 40th lesson in the second grade curriculum, again mixed between grades, and the 80th lesson, and so on. The goal was to place all students so that, to the maximum extent possible, they are always learning new material.

This approach to grouping created an opportunity. In a given school year, several groups of students would go through each lesson of the curriculum at different times. Engelmann used this to exhaustively test and refine the curriculum. After each lesson, he would ask a simple question: Did the students learn? If they didn’t learn, something needed to change.

It’s hard to get across the relentlessly high standards Engelmann had for this process. He called the end result “logically faultless communication.” If students were correctly placed in the program and the content to be learned was analyzed correctly and the instruction delivered effectively and students engaged with the lesson, every student should learn. If every student did not learn the content, the instruction was flawed and would need to be revised.3

I want to emphasize how different this is from how most curriculum is designed today. Curriculum designers typically begin with very strong opinions about what effective teaching looks like. They write a curriculum based on those opinions. They might do one round of field testing where they give it to teachers, the teachers tell them what they liked and disliked, the writers make a few tweaks, and then the program is published. When student achievement data is collected, it is often analyzed at the level of the unit or a full year rather than lesson by lesson.

Engelmann didn’t have fully-formed beliefs about all the little details of instruction when he began developing Direct Instruction. His main belief was that with high-quality instruction, all children can learn. Engelmann’s detailed vision for teaching came later, after the process of testing and refining the curriculum.

Beyond the field testing Engelmann used to design the programs, they were also validated by Project Follow Through, sometimes called the largest educational experiment ever conducted. The main part of the study began in 1968 and ran until 1977. The experiment compared a range of curricular programs on three outcomes: basic academic skills, problem-solving skills, and self-esteem. Here is the graph that people like to share:

Direct Instruction is unashamedly a "basic skills" model so it might be unsurprising that it did best with basic skills. What surprises many people is that Direct Instruction performed best with problem-solving skills and self-esteem as well. There are plenty of critiques that one could make of the study, but the evidence is still compelling. And that isn't the only research on Direct Instruction. You can read a meta-analysis summarizing hundreds of studies here.

Was Engelmann Traditional?

Direct Instruction is often described as a “traditional” approach to teaching. In many ways that’s true. The instruction is teacher-led. Lessons are scripted. There is lots of repetition and practice. The focus is on the core skills of reading, writing, and arithmetic, with an emphasis on elements like spelling and math fact fluency.

I don’t think the label “traditional” captures what Engelmann did, though. Some elements of the programs are absolutely traditional, but others are a departure from practices that are common in typical schools. A few examples:

The approach to grouping students I described above is rare. Students are assessed and placed in the curriculum based on that assessment, regardless of grade level. The programs also retest students multiple times each year, so students aren’t stuck in one group but can move ahead if they are making good progress or move back if they are not, or if they miss a large amount of school.

Direct Instruction lessons don’t have a single objective. Instead, the curriculum follows multiple “tracks” at once in parallel. This is a practice I’ve adopted in my teaching. At one time we might be solving equations with negative numbers, practicing adding and subtracting fractions with uncommon denominators, and solving geometry problems with angles. Each lesson makes a bit of progress with each of those “tracks,” giving plenty of time to check for understanding, adjust, or spend more time on a topic if necessary.

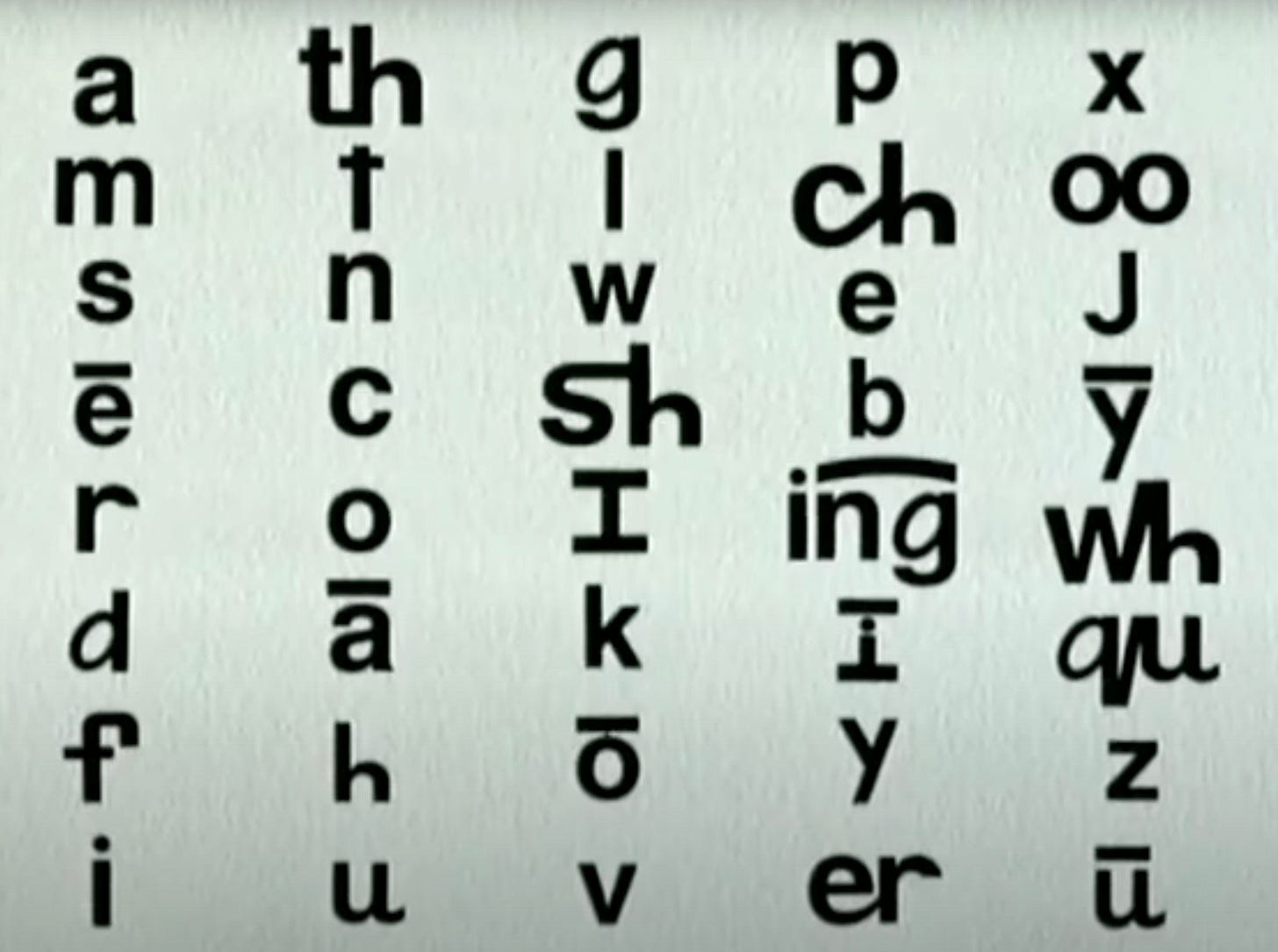

Engelmann altered the alphabet in the Direct Instruction reading programs. He observed that many young children struggle to understand the idea that multiple letters can make one sound and one letter can make multiple sounds. He used the symbols below to emphasize the different phonetic meanings of letters or groups of letters, for instance connecting the letters in th to help students see that it made one sound. This was a temporary scaffold, and over time this altered orthography was faded away to the typical English alphabet.

My point here isn’t that Engelmann was the second coming of John Dewey. My point is that Engelmann was uninterested in doing something because that was the way it was always done. If a typical teaching practice didn’t drive learning for students, he abandoned it and tried something different.

Where Engelmann Fell Short

Engelmann analyzed the content that we ask students to learn in remarkable detail, designed curriculum based on that analysis, tested the curriculum exhaustively with an incredibly high bar for success, and achieved the best results in the largest educational experiment ever conducted. Why isn’t Direct Instruction more common? Why isn’t every school using it?

Engelmann was an empiricist. He believed that the evidence for the empirical success of his programs should be enough to convince schools to adopt Direct Instruction. He wasn’t very successful. Direct Instruction is not a popular curriculum today.4

We can conjecture about why Direct Instruction isn’t more popular. Like most phenomena in education it’s probably a combination of many different factors. Engelmann judged the success of his curriculum based on student learning. I think on a broader level we need to judge his success by whether teachers and schools choose to adopt Direct Instruction. From that perspective, he simply wasn’t very successful. The details of his ideas are largely unknown in U.S. schools. You can write the best curriculum in the world. If it doesn’t get adopted and used with real students, it doesn’t do any good.

What We Can Learn

In the education world, Engelmann is largely remembered as the lead author of the Direct Instruction programs. I think far more important than the programs was the process he used to create them.

What lessons should we take from Engelmann’s work? For me, Engelmann left two ideas we need to learn from. First was his obsession with the content we ask students to learn, which lives on in the book Theory of Instruction. Second was his empiricism: testing his ideas in real classrooms with real students and iterating to figure out what works.

I think Engelmann would be uninterested with vague debates about pedagogy divorced from the content we teach. He would prefer concrete examples to generalities, so in that spirit I want to close with two examples of what I see as people working in the spirit of his approach to education.

I wrote a few weeks ago about The Writing Revolution. The Writing Revolution is both a book and an approach to teaching writing that was developed and refined by Judith Hochman in her classroom. The Hochman method is obsessed with the details of writing. All writing is made up of sentences, and the largest part of the method is focused on helping students to craft complex sentences that communicate complex ideas. Hochman has some ingenious strategies to help students develop these skills. The method goes all the way through writing paragraphs, writing essays, revising, and editing, with lots of insights into the logical structure of each activity and how to break each skill down into manageable pieces to maximize student learning. Like Engelmann, Hochman tested these ideas in her classroom for decades before sharing them with the broader teaching world.

A second example I’m learning a lot from right now is Kris Boulton’s Unstoppable Learning program. Boulton’s work is directly inspired by Engelmann’s work. He focuses on teaching math, and applies the strategies Engelmann outlines in Theory of Instruction to math classrooms. He breaks math concepts down into different types, then uses Engelmann’s ideas to design teaching strategies for each type of content. Boulton calls his approach “atomisation” and focuses on both breaking concepts down into small, manageable “atoms,” and also building those atoms up to help students solve more challenging problems. Like Engelmann, Boulton has incredibly high standards for what students can do when instruction is effectively designed. Boulton’s work isn’t a curriculum, though, it’s a training program to help teachers design their own materials in the spirit of Engelmann’s work.

Something these two approaches have in common is that they both help teachers develop expertise. Engelmann’s approach was to script lessons so that teachers could deliver the instruction effectively. Both The Writing Revolution and Unstoppable Learning focus on helping teachers analyze the content to be learned and craft their own lessons based on that analysis. This is a very different model: it puts the teacher at the center, rather than a scripted curriculum.

Neither of these approaches has scaled or demonstrated evidence of effectiveness to the point where we can say they have anything close to the record of success as Direct Instruction. These are two examples of the direction I hope education will head: away from generic teaching strategies and arguments about pedagogy devoid of content, toward the two traits I think were most important to Engelmann’s success: an obsession with the nitty-gritty details of the content we teach, and a relentless empiricism to maximize student learning.

Engelmann produced one approach to teaching that has some of the best evidence of effectiveness out there, but I don’t think it’s unique. I think what’s unique was Engelmann’s approach to the design of his programs. A perfectly reasonable person could take his approach and end up with something very different. I’m hoping education can find more people who bring Engelmann’s approach to teaching and curriculum design. We need fewer abstract arguments about teaching in general, and more work deep in the weeds of content and the concrete details that ensure each student learns.

Further reading: For an article-length introduction to Direct Instruction, I recommend this paper. The book Direct Instruction: A Practitioner’s Handbook by Kurt Engelmann (Zig’s son) is a great tour of the major ideas behind Direct Instruction. If you want a truly deep dive into Engelmann’s ideas, Theory of Instruction is the place to go next, but be warned: it is a long and dense read.

Engelmann also co-wrote the book Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons, which is a bestseller and probably the most common way regular people have heard of his work.

Something I’m doing in this post that isn’t accurate is framing the world of Direct Instruction as if Engelmann was the sole driving force behind it. Direct Instruction was not a one-man project. Many people contributed to its development, refinement, research, and dissemination over the decades. For one example, Doug Carnine coauthored Theory of Instruction and played a major role in Project Follow Through and in the theoretical foundations of Direct Instruction. Numerous other curriculum writers, researchers, and more were involved in building and studying the programs.

That said, Engelmann was there from the very beginning of the early experiments in the 1960s and continued writing and revising Direct Instruction programs for decades. He was the central architect of the original curriculum, the driving force behind the early field testing, and a primary author of many of the core programs. No one else was involved as continuously or as centrally across Direct Instruction’s full history as Engelmann himself.

Some people have a kindof allergic reaction to this idea that 100% of students can learn from effective instruction. 100% success feels at odds with the everyday experience of most teachers. I know it’s very different from what I achieve in my classroom. Engelmann recognized that 100% success was an ambitious goal based on an idealized vision of teaching and learning. That said, I think it’s helpful to contrast his approach with an idea that’s common today. I often hear teachers say that their goal is 80% success. Get to 80% success, then move on. That last 20%…well it’s tough to be perfect, and we shunt them off to intervention or special education and keep moving. Engelmann would have thought that was nonsense. He deliberately tested his programs on the most at-risk students, and himself taught a group of four- and five-year-olds whose older siblings had been identified with severe learning disabilities or were otherwise not making progress in their schooling.

For instance, here is a survey of curriculum use in U.S. public schools. The only Direct Instruction program to even register on the survey is Connecting Math Concepts, an elementary math program, at 3%. This specific survey doesn’t have enough respondents to draw precise conclusions, but we can say with some confidence that Direct Instruction programs are unlikely to be at more than 5% market share in the U.S. and are probably much lower than that in most content areas and grade levels.

I would've liked some more conjecturing why Direct Instruction isn’t more popular. If Engelmann was bad at evangelizing, that would explain why other schools didn't adopt it, but what happened to the schools that were using Direct Instruction during Project Follow Through afterwards? Did they all abandon it for some reason? And if so, why?

Hi, this was really helpful. I know you're a math guy, but any chance you have some more reading/writing examples of breaking down the components like the math example?