A Multi-Stranded Math Curriculum

A different way to organize 7th grade math

The Problem

I’ve always felt like the math curriculum moves too fast. I teach topic A, and I know students could use some more practice to consolidate their understanding. But we have to move on to topic B. And worse, topic B builds on topic A, so that shaky understanding of topic A starts a domino effect of confusion.

Practice is important. But the best way to practice is in multiple short chunks, spaced out over time, with plenty of chances to check for understanding and give feedback. With the rush to get through everything, I often feel like I don’t have a choice but to give students lots of practice all at once and then move on to the next thing.

Spending a full lesson on a topic can feel like a slog. Sometimes I realize students don’t have the foundation I hoped they did, or I sequence examples poorly, but I have to push through to stay on track.

Math is sequential. New topics build on earlier ones. But math also isn’t one giant staircase. Two-step equations build on earlier ideas of one-step equations and inverse operations, but they don’t have much to do with geometry or proportions. Percent increases build on a few different ideas, but they aren’t connected to operations with negative numbers. Still, I end up in this quagmire pushing through my equations unit so there’s enough time to teach geometry.

The Multi-Stranded Math Curriculum

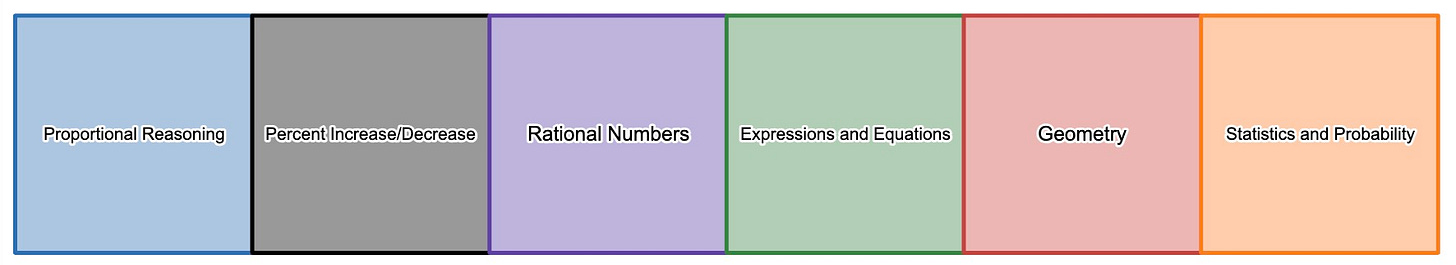

Here’s a rough outline of a typical 7th grade math curriculum.

There are six big ideas, and I teach these big ideas in separate units, one after the other. That basic approach has led to a lot of the problems I described above.

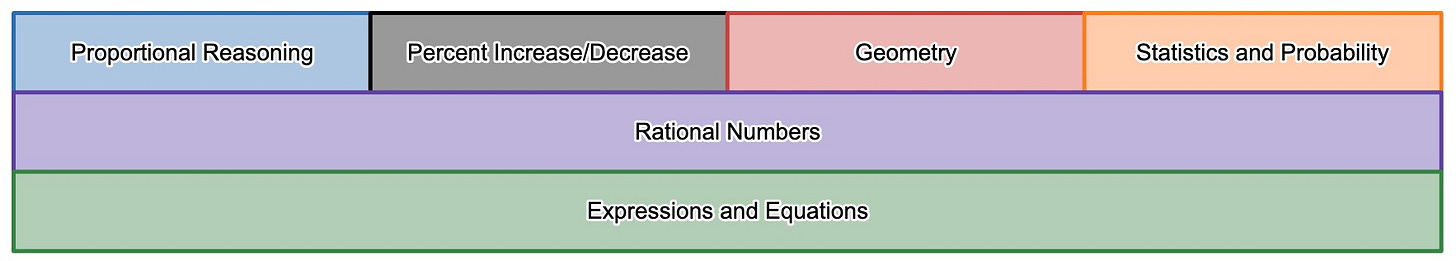

Here’s what I’m doing this year instead:

Four of the six units are sequenced a bit like before, though now there’s more time for each unit. The other two units stretch in parallel through the entire year. I call these strands, so in this case there are three main strands: the four sequential units, rational numbers, and expressions and equations.

Those bottom two units are the most important and challenging topics I teach. Rational numbers involves adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing positive and negative whole numbers, fractions, and decimals. The heart of this unit is working with negative numbers, but students need plenty of review with fractions and decimals as well.

Expressions and equations refers to both finding equivalent expressions, for instance by combining like terms or expanding brackets, and solving two-step equations and inequalities, building on work with one-step equations the previous year.

These are both tough topics. Stretching them across the entire year helps me break the concepts down into small, manageable chunks, and give students time to practice each chunk before moving on.

Here’s an example. The key representation of negative numbers is a number line. We use other representations as well, but number lines are the linchpin. So the very start of the rational numbers strand is just putting positive and negative numbers on the number line. We start with integers, and gradually get into decimals, fractions, and mixed numbers. And that goes pretty slowly, with lots of quick rounds of practice so students get fluent thinking about and moving around on the negative part of the number line. We never spend an hour doing number line problems, but a few minutes a day adds up and gives students a strong foundation — while we’re also working on other topics. All that pays off in a big way when we get to adding and subtracting with negative numbers.

Here’s another example. The biggest challenge with solving two-step equations in 7th grade is that students are supposed to solve two-step equations with positive and negative fractions and decimals. But we start with simple, straightforward equations like 2x + 1 = 11 and 10x + 3 = 43. Get students comfortable with those. Then bring in some subtraction. 2x - 1 = 11, 10x - 3 = 37, stuff like that. Then let’s spend some time practicing one-step equations with negatives, problems like 2x = -10, -10x = 40. Then let’s bring in two-step equations with negative numbers and gradually make those harder. Eventually we work in larger numbers, fractions, decimals. I’m oversimplifying a huge part of my of teaching into a paragraph but hopefully you get the idea. There’s no time in a normal curriculum to teach one small chunk, check for understanding, practice, and consolidate before moving on because it’s all go, go, go. But with multiple strands, there’s more time — I can spend a few days doing a few problems of practice and checking for understanding on the equations strand while spending most of the class on the other strands.

One key of the multi-stranded approach is that not every class is divided 1/3, 1/3, 1/3 between the three strands. Sometimes we spend a large majority of a class on one topic. Other classes are split evenly three ways. Most often there’s one “new idea” each class, and then a few quick chunks of practice from the other strands. I didn’t add it to the image above but we also do a bunch of fact fluency practice, so that’s like an extra parallel strand that runs through most of the year.

The Advantages

Here are a few things I like about this approach:

I have more time to review prerequisite skills. Sure, students were supposed to learn them last year, but students forget. Stretching out each unit creates more time to review and practice tough skills from previous years before they’re necessary.

Students have time to consolidate their learning. If I teach skill A, and then skill B which builds on skill A, I can take my time, give plenty of practice with skill A, and check for understanding before moving on. I just prioritize the other strands for a few days while mixing in short chunks of practice with a skill until students are ready for what’s next.

I can do a much better job breaking skills down into small steps. Having a single objective for each class creates artificial divisions in the curriculum. Some ideas take a class to get through, but in other places one class actually represents a few different smaller ideas. With this approach, it’s much easier to help students learn one step at a time.

Teaching multiple strands at once lends itself to spaced and interleaved practice. Practice is important, and the best way to practice is in lots of small chunks, spaced out, interleaving different skills as students become more confident. A typical curriculum doesn’t do this very well, but the multiple strands approach spaces and interleaves by default.

I teach lots of lessons that don’t go well. In a typical lesson, I push through and try my best. If that activity is only one strand of several in a lesson, it’s easy to punt. I can say hey, let’s come back to this tomorrow, and focus on the other strands for the rest of class. Then, when students are gone, I can regroup and plan a new approach for the next day.

Here’s a comparison I think is helpful. An English teacher would never create artificial divisions where unit one focuses only on vocabulary, and then doesn’t do any work on vocabulary the rest of the year, and then unit two focuses on close reading, and then no close reading for the rest of the year, and then unit three on fluency and prosody and then moves on again. Instead, those key skills are woven throughout the year. That doesn’t mean everything gets stretched out for an entire year. If you’re going to read The Crucible it doesn’t need to take the whole year, and it’s reasonable to have a unit that focuses on argumentative writing or short stories. But the most important and most challenging skills come up over and over again throughout the entire year.

Some Practical Tips

Let’s say you want to try this. Here are a few pieces of advice.

This approach to curriculum does not work if you are set on having a single objective for each lesson. If you have a principal who loves to walk in and nag you about writing your daily objective on the board...well, I’m sorry you have to deal with that. In this approach there are still objectives. I think really hard about what I want students to learn each class. But most classes will have multiple objectives, and they look a bit different. Some days the objective is to learn something new, but others it’s a quick check for understanding to inform class tomorrow, or some practice to help solidify an idea before moving on to the next thing.

Find ways to break single lessons down into smaller pieces. Take an objective and turn it into two or three smaller objectives, or introduce students to a topic and then break the practice up into a few chunks to do over multiple days. There are lots of ways to do this, but it takes practice and effort and will need to be adapted to your curriculum.

It’s helpful to have a few teaching techniques that don’t require much prep to give students some quick practice and check for understanding. I wrote about this last week, and using mini whiteboards and five-question “stop and jots” make it easier for me to give students quick practice on one strand without spending forever prepping materials.

You don’t need to go all in all at once. I started an early version of this approach because I struggled teaching two-step equations when students were still shaky with one-step equations. I would try and do some quick one-step equations review at the start of the equations unit but it always felt rushed and students weren’t solid with those skills. So I started stretching that time out, and would spend a month or two gradually working through different types of one-step equations in parallel with the previous unit. Then I started to stretch out two-step equations, focusing first on equations with whole numbers, then getting into negatives, fractions, and decimals in parallel with the next unit on geometry. Over time, I moved closer to what I’m doing now with multiple strands running through the entire year, but I didn’t go for it all at once.

Start with one topic, and pick something that’s either especially important for future years or especially hard to teach. If I were teaching 5th grade I might make a year-long strand for multi-digit multiplication and division. We would take our time working on multiplication facts at the start of the year, then gradually work into simple multiplications without carrying like 34×2 and 12×3, then bring in carrying and slowly increase the number of digits. Then we’d work on division facts, and gradually introduce multi-digit division with simple questions like 84÷2 before getting into tougher and tougher problems. If I were teaching 8th grade I might make a year-long strand for systems of equations, starting with equation solving and very simple substitutions and gradually getting harder and working through the different strategies for systems.

Direct Instruction

I learned about this idea from the book Direct Instruction: A Practitioner’s Handbook. I’ve written about the general idea previously, though that post describes a very different version of teaching multiple strands than what I’m doing this year.

A lot of people have an allergy to Direct Instruction. I would challenge you: if you don’t think of yourself as a direct instruction teacher but this idea appeals to you, you should read the book. I’m not an advocate for Direct Instruction, but I’ve still learned a ton from the program. It is very different from anything in the contemporary curriculum world, and whether or not you become a true believer, I think all teachers should understand Direct Instruction and see what they can learn from it. If you’re curious for a bit more, I wrote about what I like and don’t like about Direct Instruction here.

In the US, in the last decade, there has been a flood of new curricula that all feel the same. They’re all vaguely constructivist. They don’t emphasize practice. They are obsessed with rigor, so there isn’t much review and the difficulty of each topic increases quickly. They focus on big ideas and don’t break content into small chunks.

What I’m describing in this post feels like the opposite of the current trend in math curricula. I have felt incredibly frustrated with the two curricula my school has used in the last five years. This multi-stranded approach has felt like the antidote to all the things I hate about the curricula that are popular in the US today. If you have similar frustrations, maybe this approach is for you.

Do you have an example of what a typical lesson plan might look like with this approach? Curious to see how you roughly allocate the time within a 50-60min block, and how you avoid the feeling of being rushed within a given day's lesson.

I’m curious if you find that context switching hurts the students’ retention. I’m not sure what to expect a priori - could easily see it going either way