Direct Instruction: A Practitioner's Handbook: A Review

What is Direct Instruction, really?

This is a review of the book "Direct Instruction: A Practitioner's Handbook" by Kurt Engelmann (son of Sigfried Engelmann, one of the original writers of the program). I want to be clear about why I'm writing this review and why I think you should read it. I don't teach a Direct Instruction (DI) curriculum. I won't be advocating for a switch to DI at my school (and my school wouldn't listen to me if I did). I see a lot of conversation about DI on social media but that conversation is often vague and isn’t specific about what DI looks like in action. I want to explore those specifics. The DI programs are easy to criticize without understanding what they look like. I think teachers who feel opposed to DI should read this review, the book, or a book like it to better understand what DI is and see what they can learn from it. I hope that DI proponents are willing to hear some criticism from someone who has tried to learn about the program with an open mind.

Background

First, what Direct Instruction is not. Direct Instruction does not mean teaching by lecture. DI uses teacher explanations as a major part of its pedagogy but it is also a program focused on breaking learning down into small chunks, using choral response and cold calling to constantly check for understanding, requiring lots of practice, working on several concepts in parallel during each lesson, providing teachers with scripts to improve the quality of explanations and simplify what teachers have to think about, and placing students in the curriculum based on assessment data and not simply by their grade level. There is an emphasis on teacher-led instruction but the instruction is fast-paced and interactive, without long lectures.

Direct Instruction is different from direct instruction. The book dedicates a chapter to the differences. Direct Instruction refers to one of the programs designed using Siegfried Engelmann's ideas and approved by the National Institute for Direct Instruction. The curricula focus on literacy and math in the elementary grades and remedial programs for older students who struggle with reading or arithmetic, though there are a few other programs. The phrase "direct instruction" isn't owned by anyone in particular but the book describes lowercase di as teaching using the broader principles of Direct Instruction but outside the official programs. According to the book, Barak Rosenshine's article "Principles of Instruction" is the best concise articulation of direct instruction. The principles are here:

The book argues that Rosenshine's writing isn't specific enough to give teachers the level of guidance they need to be successful with direct instruction. The clear thesis is that only Direct Instruction programs are designed well enough to ensure that they carry out direct instruction faithfully.

Direct Instruction's claim to fame is Project Follow Through. It is often referenced as the largest educational experiment ever conducted. The main part of the study began in 1968 and ran until 1977. The study compared a number of different curricula in grades K-3 in schools serving over 300,000 children. Here is the graph that people like to share:

Direct Instruction is unashamedly a "basic skills" model so it might be unsurprising that it does best with basic skills. What surprises many people is that DI performed best with problem-solving skills and self-esteem as well. There are plenty of critiques one could make of the study — it only looked at the lowest grades, the selection was not randomized, there was a lot of variation between sites in how well DI performed, and more — but the evidence is still compelling. And that isn't the only research on DI. There have been hundreds of studies of DI which find positive results. The book All Students Can Succeed is often referenced as a good summary of that research, though I haven't read it myself.

Some things I found interesting

Here are some things I learned that I either found interesting or didn’t expect before reading the book:

A Direct Instruction lesson does not have a single objective. Instead, the curriculum works on several “tracks” at once. Each lesson has several small chunks of instruction on different tracks so that each track continues moving forward. For instance, a math lesson might work on adding and subtracting fractions with common denominators, representing fractions visually, finding common multiples of pairs of numbers, and writing equivalent fractions, all working in parallel toward the bigger skill of adding/subtracting fractions. These skills tie together, and maybe there would be another track beginning work on a skill that comes next. The idea is that skills aren't isolated from each other but are interwoven, that a lesson is broken up into lots of small chunks to maximize engagement, and that practice with each skill is extended over a longer period to improve retention.

Direct Instruction involves tracking students based on their performance on pre-program assessments and regular mastery checks embedded in the program. Students are not grouped by age. The assessments attempt to determine the exact spot in the program where each student’s knowledge fits and the school puts them with a group as close to that spot as possible. Student groupings are flexible and may change multiple times a year to keep students working at their level. The book is very clear: if a school does not use this type of precise and flexible grouping, they should not expect the Direct Instruction program to work.

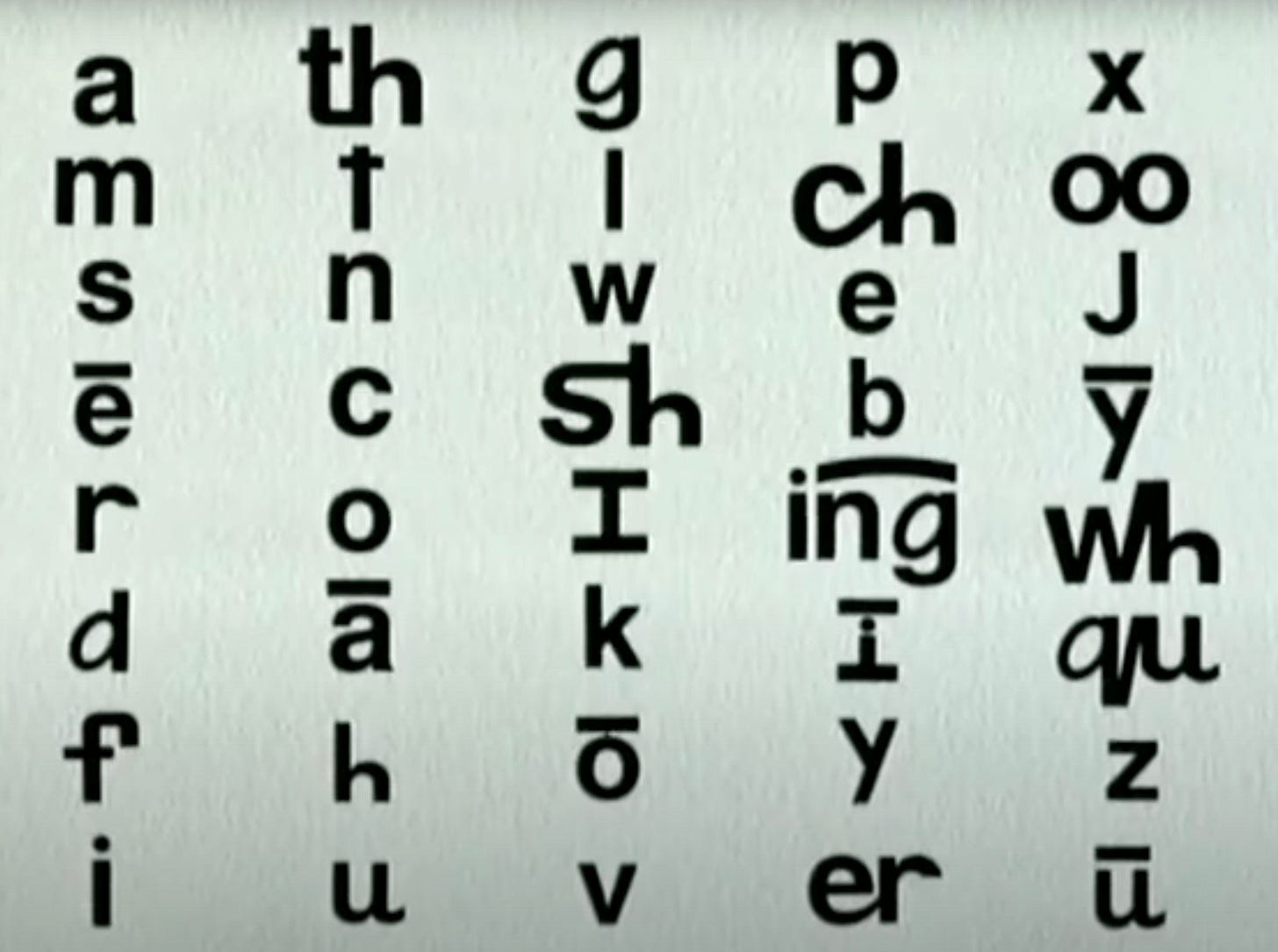

Each Direct Instruction lesson comes with a script. The book calls their method of explicit teaching “faultless communication.” Many teachers hear “scripted curriculum” and immediately think that it turns teachers into robots. That’s reasonable, I think building explanations is an important part of preparing to teach a lesson. The premise of DI is that each explanation is designed with a carefully sequenced series of examples and non-examples that maximize the likelihood of learning. I think that the typical curriculum in use today doesn’t put enough effort into suggesting “here is a good way to explain this idea” and teachers would benefit from that type of resource. DI goes even further in some areas. For instance, DI uses an alternative orthography to teach students letter-sound correspondences. Joining multiple letters that make a single sound, altering similar letters to make them distinct, and adding accents to clarify differences in vowels all help beginning readers decode words. These are gradually faded back to regular letters as students master decoding skills. Putting that level of thought into explaining ideas in ways that make sense to young children is pretty cool.

The other important clarification about the scripts is that just because a lesson is scripted doesn’t mean it happens the exact same way every time. The scripts include lots of places in each lesson where the teacher should adjust what they do next depending on how students do with a question or mastery check.

The programs have a clear focus on outcomes rather than perfect fidelity to the program. Over and over again the book emphasized that if a teacher’s students are successful — if they pass mastery checks and move through the program at a speed where they stay on or get to grade level expectations — school leadership should allow deviations based on the teacher’s judgment. I would love to hear more of this in schools. I hate when schools tell teachers to implement a curriculum with fidelity without seeming to care whether the curriculum is working.

One of the core principles of Direct Instruction is that students should experience a high success rate, where they know how to answer a large majority of the questions they are asked. Each lesson is 80-90% review. Students get lots of chances to practice things they learned the day or week before and build confidence with ideas that they know before introducing a new idea. DI sees this as a core motivation strategy: students like to be good at learning. Planning for a high success rate and incorporating a lot of review motivates students to engage, improves retention, and avoids overwhelming students by introducing too many ideas at once. This also means that missing a day or two of instruction is less of a big deal than in a typical curriculum.

The Direct Instruction programs have an interesting approach to checking for understanding that I hadn’t heard of before. They call it “first time correct.” The goal is for students to solve a problem or answer a question correctly the first time they see it in a lesson. A DI lesson wouldn’t put much stock in an exit ticket-type question because the students were just working on that skill; getting an exit ticket right isn’t a great predictor of whether a student will remember an idea the next day. Instead, getting a question right at the start of a lesson the next day without any review or preparation is a better signal that they understand and will retain the concept.

Some concerns

Here are some concerns I would have if I were asked to teach a DI curriculum:

The overall philosophy seems like it's rooted in teaching early reading skills. Early reading curricula and reading remediation seem to be their best-selling programs. But I can't understand why, if there is so much research that DI is successful, there aren't more curricula for higher grades. Most programs don’t go past 5th grade. Direct Instruction has existed for over 50 years. What's going on? Why isn't there upper middle school or high school science, or social studies offerings besides US history, or reading programs that go into middle or high school, or math beyond Algebra I? This isn't addressed in the book and honestly seems like an admission that DI programs only work for younger grades and simpler skills. The contention that only true Direct Instruction programs work seems like a major problem. If Direct Instruction is so great and other curricula don't cut it, why aren't there a broader range of DI programs?

DI programs are meant to be flexible. Teachers constantly assess students and adjust instruction. But most of those adjustments are actually just repetition. If students struggle with an exercise they do the exercise again. If students fail a mastery check the teacher might repeat the full lesson. If students fall consistently behind they are moved to a different group and repeat a larger section of the curriculum. For some simple skills this makes sense — if students struggle to differentiate between "b" and "d" sounds, it makes sense to go through it again. But if students are struggling to identify a character's motivation in a story or to solve a proportional reasoning problem, repetition isn't the right move. Students will learn that specific character's motivation or the answer to that specific problem but not the general principles they need to do similar thinking in a different context in the future.

Direct Instruction seems uninterested in student thinking. The programs have been called behaviorist in that they are only interested in the outputs of teaching. The teacher delivers the lesson and elicits answers from students. If the answers are correct students are praised and the lesson moves on. If the answers are wrong the teacher repeats the activity. The program is not very interested in building on what students already know, using student thinking or intuition as a resource, or hearing different perspectives on a complex idea.

Student participation seems almost entirely limited to three modes in Direct Instruction: choral response, cold calling (the program calls this "individual turns"), and independent written assignments. That feels narrow to me. Why not turn and talks? Why not partner work? Again, I see the influence of early reading instruction here. If I want students to learn the difference between two sounds, choral response and cold call are probably good strategies. If I want students to learn how to solve proportional reasoning problems, choral response isn’t going to cut it; having students put the ideas in their own words is a key part of learning more complex concepts and communicating in an unstructured way with another human being is a good way to do that.

Direct Instruction has a narrow view of motivation and joy. The program is very clear: they believe that students are motivated to learn when they feel successful mastering skills. That is one theory of motivation and I don’t disagree with it, but I think it’s incomplete. I wrote a piece a few weeks ago about all the ways I try to help students see that math is awesome — talking about what mathematicians do, telling stories about math, finding math in unexpected places, and more. One part of my motivation repertoire is helping students feel successful at math but there are lots of other reasons to want to learn math. DI doesn’t make room for any of that.

Closing

One reason I wanted to read this book and learn more about Direct Instruction is how I see it represented on social media. To some people Direct Instruction is the pinnacle of education. These people tend to omit the fact that DI focuses almost entirely on elementary grades, talk about the programs in vague and general terms, and gloss over any questions about Project Follow Through. On closer examination DI isn’t the universal panacea it’s claimed to be, and it’s reasonable to have concerns about different elements of the program. On the other hand, some folks characterize DI as robotic teaching creating robotic students, focused only on rote learning. While I understand that criticism, I learned a lot from the book and there are lots of parts of DI that I found to be thoughtfully designed, some of which I want to incorporate into my teaching. Like most things in education, it’s more complex than it seems on the surface.

I’m not trying to convince anyone DI is great or DI is bad. More than anything I want people to understand what DI is, and what it is not. Reasonable people can disagree about the curriculum, but those conversations are only reasonable if we know what we’re talking about.

I've always wondered about the actual pedagogy of DI, versus the edu-zeitgeist commentary. Thanks for doing this deep dive.

Thank you for this! My colleagues and I read the book How Learning Happens by Paul A. Kirschner this year. They mentioned DI in the book and compared it to di, but I was unfamiliar with the backstory of the concepts. Your article cleared up that confusion for me! Thanks for the info. (Btw, I would highly recommend How Learning Happens as an excellent exposition of educational research.)