Math Is Awesome

And how to help kids think math is awesome

I think math is awesome and I want students to feel that way too. What’s the best way to convince students that math is awesome?

I don't want to put all of my eggs in one basket. There are lots of things that are awesome about math and I try to give students lots of different ways to have positive experiences in math class. One approach that seems to have become more popular in the last few years is to do lots of creative and open-ended math tasks for the first few days of the school year. A lot of this is the influence of Youcubed's Week of Inspirational Math. It’s not my style — I do some activities like those but I try to spread them out throughout the year. I also don't want to rely on one activity or one week to convince students math is awesome. I want to give students lots of different, bite-size chances to see what math can be, to spread those out, and to provide as much variety as I can. Not every student will like every activity; the goal is to give every kid a few, or maybe a lot of, moments where they say “hey, math is kindof awesome.” Here is a sample of what I try to do:

Puzzles

Every day my class begins with a five-question Do Now and a puzzle. The questions are on the board and students pick up a handout that looks something like this:

The puzzle shown is a "number snake" via Matt Enlow. We do one type of puzzle for 4-6 weeks, starting with simple ones and getting progressively more complex, then switch to a new puzzle. Naoki Inaba's puzzles, which Sarah Carter has collected here, are popular, especially the shikaku ones like this:

Routines

I wrote in more detail about these here. After the Do Now we do some sort of math thinking routine. This might be a Which One Doesn't Belong, or a visual pattern, or a slow reveal graph. We stick with each routine for 3-4 weeks before moving on to a new one. These are short and give students an opportunity to think about math in a different way than what we usually do.

Mathematicians

Once a week I share a mathematician with my students. I started this inspired by the Mathematicians Project, trying to show students that mathematicians aren't just white dudes. That's still a goal, but I've realized this is also a great opportunity to show students the range of things people do with math and to broaden what it means to be a mathematician. Last week was Emmy Noether, and I told them about how while symmetry might seem simple it actually plays a really important role in physics and astronomy, and how Noether's work was the foundation for Einstein's discoveries. This week will be Chika Ofili, a Nigerian boy who, at 12 years old, discovered a new divisibility rule for 7. Next week will be Diana Ma, a data scientist who works for the LA Lakers.

Exploration

One part of math is figuring stuff out and feeling the joy of discovery. For a while I tried to do this on an everyday basis, getting kids to discover the math we were learning. I've moved away from that. The reality is that orchestrating discovery every day is really hard, takes tons of time, and it's often the same kids who are figuring it out. Instead, I try to bring in occasional non-curricular tasks. PlayWithYourMath is a great resource for this. We don't explore every day or every week. I try to focus on quality over quantity and give students some occasional, well-designed chances to experience mathematical discovery and explore an interesting math problem.

Challenge Problems

I wrote here about how I organize challenge problems for my students. These are great ways to challenge kids who finish early and give them something to do besides help other kids or solve the same problems with bigger numbers. Last week we did the Foxtrot Nerd Search!

Stories

There are so many great stories about math, from the geometry of circles to young Karl Gauss being asked to add the numbers from 1 to 100. I wish we had a repository of short, interesting stories about math for teachers to draw from. Humans love stories, and stories should play a role in math class.

Celebrate Ideas

I want students to feel like math class is a place where their ideas are valuable. While students are working on a problem or problems I do my best to listen in for new perspectives or unique approaches, then ask students to share those with the class. Kids are full of ideas, and telling a student “your idea is worth sharing” is an important message for everyone to hear at some point.

Math in Surprising Places

This last one is a bit fuzzy but social media has been a great resources for finding math in unexpected places. Last week we did Robert Kaplinsky's “How Much Money Is That?” lesson.

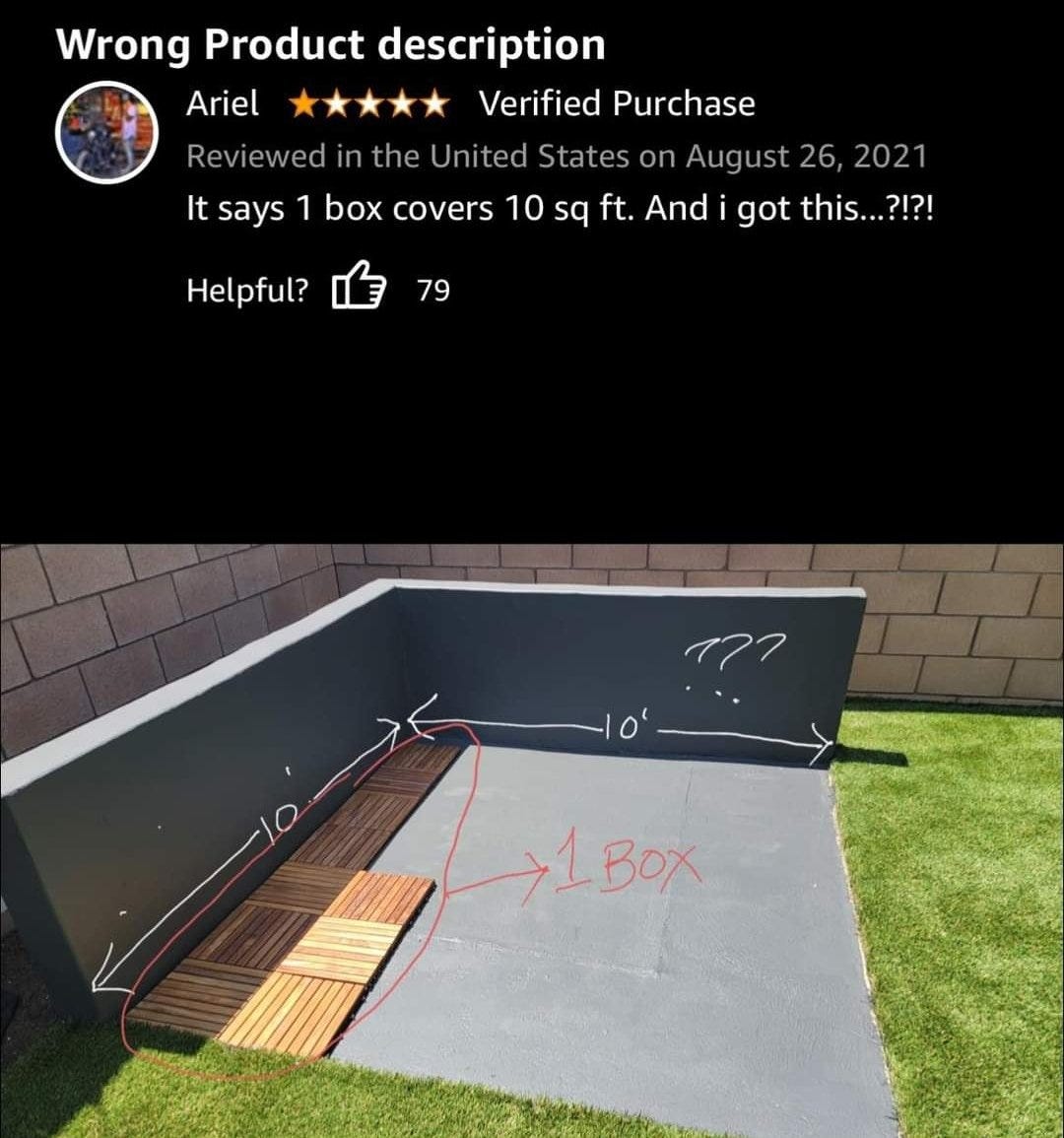

While working on area I showed my students this:

It's not something I can do in every lesson but when the opportunity comes up it can be a ton of fun.

None of these ideas is a magic switch that makes kids love math class or think math is awesome. Every kid is different. But with a lot of different ways to enjoy math it's more likely that each kid will find something they like, something that makes them say "whoa this is cool." It won't be every kid or every day. It's taken me years to accumulate all these little pieces, but it's been a great project and one I will continue in the future.

A final note. I've been on a bit of a kick recently writing about cognitive science, memorization, that type of stuff. There's a stereotype that teachers who care about memorizing times tables don't care about the beauty and joy of math. That's not true! You can do both. I’d argue they work together. Ignoring foundational skills sets students up for frustration in the future. It’s hard to like math class if you are always struggling. But only teaching foundational skills and never showing students why math is awesome, why those foundational skills are worth learning, is also a recipe for frustration and disengagement. I try my best to balance both of those pieces of math class.

Quanta magazine’s Hyperjumps was a great hit in my class the last month.

I've started giving my students the number snake puzzles regularly and they like them! Trying the shikaku puzzles next.

Also, I love the 10 square feet one star review photograph. Thanks for sharing all this good stuff!