A Nice Worksheet

Connect each problem to the problem before it

This is the third annual version of my “nice worksheet” post. It’s one of my favorites. Worksheets are great. You can check out last year’s here, and the year before here.

A lot of math teachers hate worksheets. I understand why. There are lots of terrible worksheets out there. Worksheets that feel tedious, that are too hard, that make students feel dumb, that don’t result in much learning.

But worksheets are really just math problems on pieces of paper. Those are great tools! We should give students math problems, and we should have them solve many of those problems on paper.

This is a post about a nice worksheet. Worksheets are easy to hate, and I think it’s valuable to describe what an effective worksheet looks like.

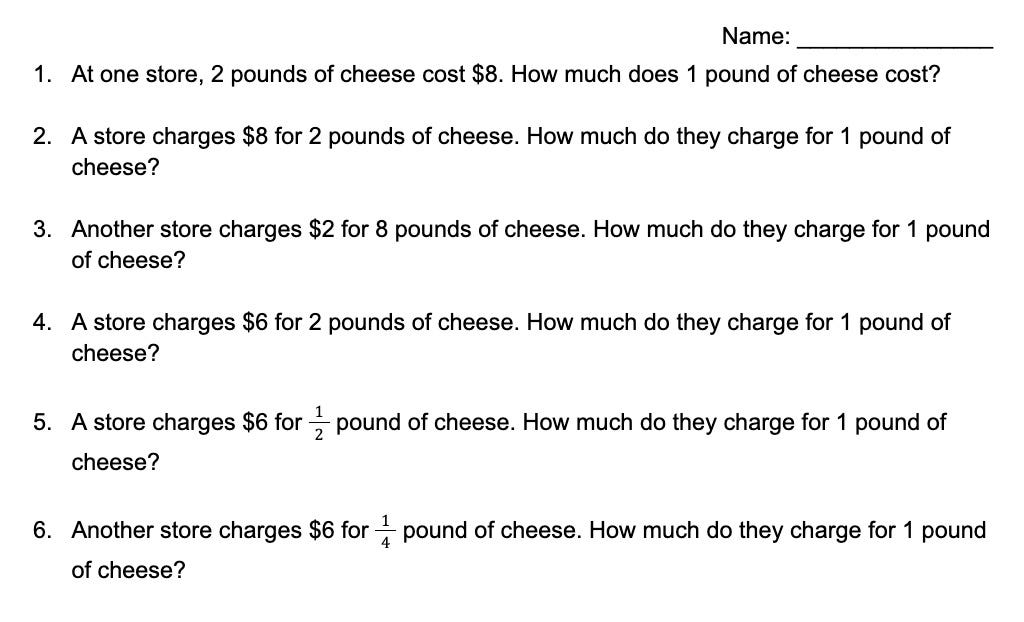

The worksheet (I gave students more space on the actual worksheet, which you can see here):

Here are a bunch of random reflections on this worksheet.

Each problem only changes one small thing from the previous problem. This means students can focus their thinking on the part that changed, rather than starting from scratch each time.

The problems start simple, helping students build confidence before they get to the tougher stuff.

The problems get gradually harder over time, but only in very small steps. This means that if students can get started, they can often connect each problem to the problem before it, allowing them to solve harder problems than if I jumped to the toughest problems all at once.

In math teaching, we often talk about the problems we give students. But often, much more important than individual problems is the sequence of those problems. I could give these problems to students in a different order and it would be a disaster.

When students work through these problems, I can see very specific places where they struggle and respond quickly. If a student gets #3 wrong, they are confused about one very specific part of finding unit rates that I can address. If a student gets stuck on #5, it’s the fractions that are tripping them up.

This general style of worksheet is one I’ve been using a lot recently. I start with something I’m reasonably confident students know. In this case, we had already done a bunch of problems on unit rates. The problems get gradually harder from there. Students can see how these harder problems are connected to problems they know how to solve. I can see where students get stuck and provide more support or figure out which ideas we need to spend more time on.

I know I have some readers who are big fans of Direct Instruction, and others who are big fans of Building Thinking Classrooms. Those are two very different approaches to teaching. But both approaches endorse something very similar to what I describe above. The Direct Instruction folks call it an “expansion sequence.” The Thinking Classrooms folks call it “thin-slicing.” I don’t care very much what you call it. I think it’s a good idea! DI and BTC teachers use these problems very differently, but the basic structure and sequence of the problems are very similar. A great thing to do in a math class is to start with a problem students generally know how to do, then gradually ask harder questions, each connected to the last, and see how far students can go.

The most important variable in whether this worksheet goes well is what students already know. We had spent some time solving simple unit rate problems, so I felt pretty confident students would do fine with the first few questions. We had also just spent a bunch of time working on fraction division, especially problems dividing a whole number by a unit fraction. We hadn’t put the two together, but students had all the pieces to try these problems.

I don’t give students the worksheet and then assume they’ve learned this topic, and they can find unit rates with fractions forevermore. My mental model for teaching with a worksheet like this is that it’s just one in a number of sequences:

Before this, students solved a series of increasingly difficult unit rate problems without any fractions. Then I give them this worksheet. Then we did another, but started a little tougher and mixed in more complicated fractions. Repetition is good. My students will see a few different worksheets like this.1 If I’m successful, each one be a little harder than the last, and students will become a bit more confident each time.

I don’t spend very long on these worksheets. I might start by asking students a few quick questions on mini whiteboards to make sure students know the basics of unit rates. That helps me make sure students are ready for this worksheet, or identify a few students who will need some help getting started. Then I might hand out the worksheet and give students four minutes to see how far they can get on their own. Then I might give students a minute or two to compare answers with a partner — if I’m noticing a common mistake, I’ll direct students to discuss that problem with their partner. Then we come back together and discuss those problems as a class. Maybe we spend a few more minutes working on the problems. Maybe I’ll give another question on mini whiteboards to stamp what we discussed, and then we move on.

I explain things to students. I think explanations are good. But I don’t think teachers should explain everything. First, trying to explain everything takes forever and doesn’t leave any time for students to do math themselves. Second, students like applying what they know and figuring things out. This type of worksheet is a nice way to see what students can do, and to offer explanations when they are needed without spending all my time explaining every possible idea to students.

For folks who are interested in how effective AI is at making materials for teachers: after making this worksheet, I gave the worksheet to an LLM and asked it to create a similar one, with some pretty extensive guidance as to the structure and goals of the worksheet. It gave me a bunch of problems like: “A library charges $4 for 1/2 of a book. How much does it charge for 1 book?” It followed the structure of the word problems I wrote perfectly, but in a context that doesn’t make any sense. I tried to get it to give me a different example and it ended up using the same one again. Then I gave up and moved on. This is a good example of the type of issue I have when trying to use LLMs to make materials. If I want some simple repetitive practice, AI might be a good choice. But if I care about the details of the structure and sequencing of the problems, AI often comes up short — and in hilarious ways. Maybe I should have written a better prompt, or tried a few more times, or tried a different company’s model. But my hesitation with AI is that I can usually just write this stuff myself. It would take me longer to get AI to do this for me than it would for me to do it. And that time I spend thinking about the problems I give students is valuable. It’s a chance for me to reflect on what I want from the lesson and why I want the lesson structured in a certain way. If I start having AI think for me, I worry I’m not going to grow as much as a teacher.

I really like your point about how this format allows you to respond quickly because you get information from seeing which question students are stuck on. Being able to make the feedback process more efficient in the moment is a game-changer during practice.

Honestly appreciate your low-key, practical effort to de-stigmatize math problems on a piece of paper aka a worksheet. I also appreciate the lesson structure details; lead in with some related mini whiteboard work, then giving students just a few minutes to work on the worksheet, see how many they can get done, compare their work with a partner, you monitor and use it as formative data to provide feedback in real time, and then move on the next task. Good chunking of work and variability for engagement. Might have to use this as a basis for a “How to use a worksheet well” set of guidelines for teachers in my district.