I was on my district’s committee to adopt new math curricula for K-5 and 6-8 last year. It was pretty interesting. We looked at a bunch of different curricula at both levels and I talked to teachers both within and outside the district to hear what they look for in curriculum and what different curricula are like. I want to write about a few big-picture trends I'm seeing.

I’m going to avoid naming any specific programs in this post. I don’t want to get into a back-and-forth with people about how their favorite curriculum is actually really great and my criticisms don’t apply. I’m describing general trends. I’m not saying everything in this post applies equally to every single program. The point is “if you are adopting or implementing a new curriculum, here are a few things to watch out for,” not “all of these are iron truths of every program on the market right now.”

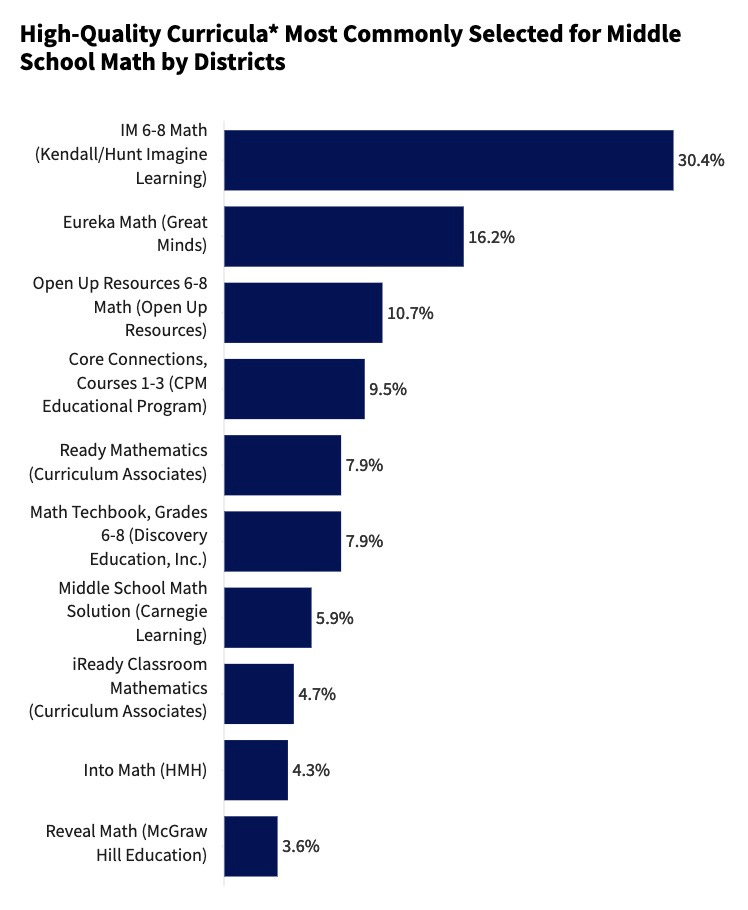

First, there are lots of new curricula out there. Here is some survey data1 about curriculum adoption. Many of the most popular curricula have been released or substantially updated in the last few years, and I'm sure those newer releases will continue to gain market share as more districts go through their regular adoption processes.

Here are the trends I’m seeing:

Rigor

The most important thing to understand about curriculum today is how much it is driven by EdReports. EdReports is an independent organization that rates curricula. Somehow it became the de facto gatekeeper. Most districts won't adopt if the curriculum doesn't meet EdReports criteria. But the criteria are really focused on one thing: does the curriculum reflect rigorous, grade-level math?2

It's good to make sure a curriculum is rigorous! Rigor is often a weakness of teacher-created materials because it's hard to know exactly how hard questions should be for a given topic — standards are typically too vague, and there aren't many user-friendly resources out there to help benchmark rigor. So the big positive thing I can say about most contemporary curricula is that they do a good job of matching expectations for grade-level rigor.

Scaffolding

The focus on grade-level rigor has a downside. Every curriculum I looked at didn’t really create on-ramps for students who were lacking skills from previous years. I think this is a downstream effect of EdReports. They're all being graded on focused, coherent, grade-level expectations, so everyone is scared to scaffold challenging skills with a lesson or two that reviews math from last year. Those types of “bridge” lessons can be really important for students to succeed with grade-level content, but they might get docked for lack of focus or whatever so most programs don’t do it. Particularly after covid school closures there are lots of students who are missing skills from last year or years before. A bit of reteaching of skills students often struggle with, then gradually building from there to grade-level goals, is key to avoid leaving students confused. Every curriculum I looked at either didn't provide resources to create an on-ramp for those students, offered one or two quick problems then moved on, or buried resources away somewhere hard to find.3

Practice

Conceptual understanding is a big priority of all these new curricula. That's great! I'm in favor of conceptual understanding. But somewhere along the way all the publishers seemed to decide that, since they focus so much on conceptual understanding, students don't need to practice as much. Across the board, curricula put less emphasis on practice or they bury practice in an online program of dubious quality.4

The lack of scaffolding and practice alone don't necessarily mean that a curriculum is bad. Planning mini-lessons that fill in the gaps and adding extra practice are things teachers have done forever. I would love to see more of those things included in a curriculum but it's not an insurmountable problem. Still, they’re important to watch out for, and they play into the next two issues I’ll describe.

Fidelity

I don't know how principals and superintendents decide this stuff, but in the last few years lots of schools decided that their teachers need to implement the chosen curriculum with fidelity. This isn't happening everywhere, but more and more schools are giving teachers a pacing guide that tells them which lesson they should be on each day. I think this is bad. Is a little bit of accountability around long-term planning a good thing? Yes. But teachers should have the flexibility to say, "hey, my students really don't remember the fraction stuff they learned last year, I want to take a few days to reteach that before launching into this unit." That's one of the best adjustments a teacher can make to help their students succeed. More and more districts are making that impossible.

Overstuffed Programs

The final issue, which plays off the others, is that many (not all! but many) of these curricula are absolutely stuffed to the gills with every hip fad from the last decade. They do number sense! And fluency! And STEM applications! And growth mindset messages! And math history! And engaging videos! And online diagnostics! And social-emotional learning! And manipulatives! And differentiation! And student agency! A lot of it is nonsense. In many cases there's good stuff tucked in there, but it's hard to separate the wheat from the chaff. The educonsultants working with my district recommended that the elementary schools wait to implement the fluency module in their curriculum for the first year or two. I was dumbfounded. No fluency? For two years? But the curriculum is so stuffed that something has to give.

I think in many cases this is the straw that breaks the teacher's back. Teachers can provide extra practice, and add mini-lessons to fill in stuff students forget, and work their way around pacing guides. But when the curriculum is full of so much stuff , there's suddenly no time for all that. It’s a ton of work just to figure out how to use the core components of the curriculum, and it's a race just to stay on track and finish by the end of the year.

I’m spending some time this summer preparing to teach my new curriculum. I’m pretty sure my school won’t give me a pacing guide, and if they do I will politely tell them to fuck off. I’m the only 7th grade math teacher here so I have lots of flexibility. I’ve taught this grade level for three years now so I have a pretty good idea of where I need to supplement, and a few different tools to draw on for extra practice. I think I’ll be ok.

Something I would love more schools to understand is that curricula are really just big collections of math problems. Sure, they have some fancy model for what they want their lessons to look like. But every teacher interprets and implements a curriculum in a different way. The backbone is the problems. I feel confident that the problems in my curriculum are rigorous. That’s great. I’ll have to add some more problems to review and reteach the topics my students are rusty on — practice with dividing fractions before we get to unit rates with fractions, practice with angles before geometry, and so on. I’ll have to add more practice for many topics. And I’ll have to ignore a bunch of the fluff. That’s all fine. I hope more schools will give teachers that kind of flexibility, to take the curriculum they’re given and make it work for their students.

Note that this data is only looking at curricula that are rated “high quality” by EdReports, which represent 45% of elementary schools and 40% of middle schools. There’s a bit more information about other programs in the report itself. The best way to look at this data is that these are the most popular programs being adopted right now.

Technically the first two standards for EdReports are “Focus and Coherence” and “Rigor and Mathematical Practices” which are mostly different ways of saying grade-level rigor. There’s a third standard for usability but I saw some ridiculously hard to use curricula get high scores on usability, I don’t know what’s up with that.

If you suggest to the wrong person that the curriculum needs more scaffolding you’ll get a condescending lecture about how, if you implement the program with fidelity, students will have remarkable recall of what they learned the year before and won’t need that scaffolding.

If you ask too many questions about this you’ll hear about how, if students really understand it, they don’t need to practice it.

I love what you said how curriculum is “a big collection of math problems.” Personally, that’s all I really need! I’m always hunting for good problems that are rigorous and make students think. I don’t need a strict lesson by lesson pacing guide, or the pressure to use the curriculum materials “with fidelity.” It’s too bad you’ve noticed a trend in districts requiring that, thankfully I’m in a district where we have that flexibility.

Thanks for sharing, great post!

Woo hoo!!! I need to celebrate for a moment!

When I had my first teaching job back in 1999 (I was teaching in the 20th century, you young'uns!) there were few resources available for conceptual, creative teaching. All the textbooks I ever saw were pages of facts and examples, followed by long, long lists of problems. Any creative, student-centered ideas would have to come directly from the teacher themself. I held onto my Marilyn Burns tightly, and was overjoyed when I discovered MARS. But neither was particularly good at helping me with my Algebra II class directly.

The American curriculum was always faulted for being a mile wide and an inch deep. The textbooks were always too much, too big, too long. I heard it blamed on the various states: the book needed to cover these three topics that were required in Texas, and those four for California, and next thing you know there is 15 chapters and a teacher could only possibly cover six of them. This question of "not enough practice problems" was certainly not on the table -- practice problems were all we had.

So when you complain that the material is too tightly concentrated at grade level, and does not have enough practice problems, well, I have to take a moment to celebrate. For a teacher who wants to engage students using math, and mix conceptual work with fluency, this is a great step forward. It is easier to find a good scaffolding lesson (try last year's book, for example) or practice problems (IXL, Khan, etc) than it is to make up all the conceptual lessons and real-world examples on your own.

Really, I never thought we'd be here. I never thought that "not enough practice problems in the textbooks" would be the complaint. We've turned a corner. Although not everyone is in agreement about what math should look like, this is still a major milestone.

Next steps? I love your assessment here, that we need easier access to scaffolding lessons. That districts need to give teachers more leeway. (I would add: district also should provide teachers with the type of coaching that helps them see the value in the materials provided -- many don't). Overstuffed programs -- yeah, it's not new, but it's annoying too. Let's work on that as well. CMP and IMP provide interesting templates in that direction, having paved the way where the big publishers now take charge.

Thanks, as always, for sharing your insights, Dylan. Hope you enjoy the rest of your summer.