I sometimes hear a sentiment that goes something like, "Of course it makes sense to group students by ability. Everyone will learn more if they learn at their level."

That might sound like common sense, but the reality is a lot more complicated.

My thesis in this post is a bit messy. It’s something like, "while tracking isn't necessarily bad, typical tracking practices don't actually do much to help students learn at their level. Schools should be more thoughtful about the menu of options they have to work with and focus less on tracking vs not tracking." This isn’t an anti-tracking post. I want to explain how tracking can be done well, but also the limitations of tracking and the wide array of options beyond conventional tracking.

If I were to generalize broadly about the vibes of the last 20 years in American education, one big thread was a push for differentiation in mixed-ability classrooms rather than between-class tracking. It seems like today there is a vibe in the opposite direction, an acknowledgment that differentiation is a huge amount of work and isn’t very effective. Broadly speaking I agree with that sentiment, but I worry that a push toward tracking will lead to shallow, simplistic solutions to a hard problem.

Context

In the US, grouping students by ability is often called "tracking" and that’s the word I’ll use in this post. Tracking comes in lots of flavors, and it is a decision often left up to individual schools or districts. That means practices are all over the place. Tracking is a common target for school reformers of all stripes, and tracking has waxed and waned with the tides of various school reform movements.

While writing this post I'm imagining middle school math classes. Tracking is less common in elementary school, especially in the early years, and the reality is that gaps in academic achievement are smaller in elementary school and there's less demand for tracking. When students are grouped by ability in elementary schools it is often within classes rather than between classes. In high school tracking is much more common, but it's also harder to generalize because high schools can be so different from each other.1 Math is my subject and is also where fights about tracking tend to be the most intense. These arguments apply to some degree in other subjects and grade levels, but middle school math is where they are most visible.

Why I'm a Tracking Skeptic

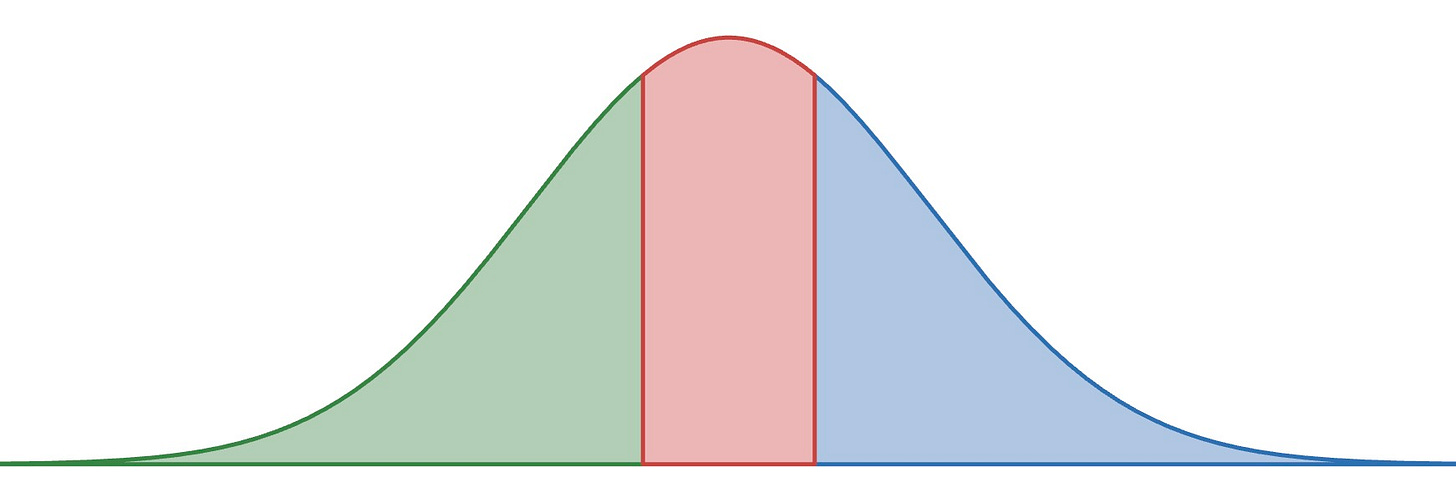

Here’s a bell curve divided into three sections with equal area:

The most common form of tracking in the US is a three-tier system. You take all the students in a given grade, and based on a combination of test scores, grades, and subjective teacher judgments they are put in three roughly equal groups. You might think: this makes sense. Now teachers can adapt to meet each group where they're at. Right? The bell curve gives you a hint as to why that’s easier said than done. The middle group has a lot in common. But the left and right groups have a huge spread of academic achievement (or whatever variable you’re trying to measure).2 The kids in the middle were already working on their level, and the two groups on either side have a huge spread within them and are at a wide range of levels.

And grouping is much harder than drawing some lines on a bell curve. First there's measurement error. The tests we use are, at best, accurate to within 10 percentiles — more like 20. So there are a few 50th percentile students in the top group. Then you have subjective teacher judgments, some students pushed into the stronger class because they are compliant and well-behaved, some students pushed down because they're rambunctious. There are logistical challenges — maybe you need students in the same groups for math and English, so you take an average of the two but some students are misplaced for one or the other.3 You have a few parents who really really really want their kid to be in the highest group and the principal gives in. All of a sudden you have a bunch of 40th percentile students in that top group. So this class that's supposed to meet students on their level has students from the 40th percentile all the way to the 99th percentile. Now this group can go a bit faster than a "regular" math class, sure. I'm not saying there's no difference. But if you have a fantasy that your bright, 80th percentile kid who's bored in regular math is going to be challenged to move as fast as they can in this tracking system, you might be underwhelmed by the results.

There are tweaks you can make around the edges — multiple assessment data points, less subjective judgment, stand up to parents. You can fiddle with the number of groups and the number of students in each group. But you're left with the same basic reality: sure, you'll get some extra learning from that top group. It's not nothing. But it's a lot smaller than you might like to think. And you aren't actually meeting each student where they are.

Then you've got the middle group. No issue here, this group gets the same curriculum as normal, there are fewer bored kids and fewer who are clearly struggling with the material.

And then there’s the lowest-level group. This is where the argument against tracking comes from. These classes are often sad places to be. Unfortunately, they are often assigned to the least experienced teachers. Students know which track they've been placed into, and they act like it. The teacher can do their best to provide some extra support, to give students extra help with foundational skills. But in American public education, one of our dogmas is high expectations. And high expectations means that we teach every student grade-level math. The origins of that ideology are beyond the scope of this post, but the outcome is straightforward. You've grouped together students who, on average, need more support, are less motivated, and feel frustrated at school. And while you could meet these students on their level by taking a step back and beginning with some easier content, that goes against the dogma of high expectations. Those students are often taught more or less the same material they would be taught in an untracked class. In many cases, the teacher tries to teach the same curriculum and just doesn’t get through everything, which is the worst of both worlds: trying to keep up with grade-level content, but coming up short.

One final issue is that families often have strong opinions in favor of tracking. But families can’t see what’s happening in classrooms. So a school has tracked classes, the concerned parent gets their kid into the highest-tracked class, and they feel like their work is done. They might never realize that the higher-tracked class is learning the exact same content as everyone else. They don’t have access to any way to compare. So there’s an incentive for schools to institute some form of tracking, but often not to substantively change the learning experience between the tracks.

Tracking can be done well. Teachers can include more challenge problems and move faster in a higher-tracked class, and provide more scaffolding and support in a lower-tracked class. Tracking can also be done poorly, where all three tracks just get parallel experiences in different classrooms.

Other Options

The main point of this post is that lots of people oversimplify tracking. “Oh yeah, obviously we should track so students learn at their level.” But it’s harder than that. And there are a bunch of options that can either substitute for or supplement the most basic form of tracking I described above.

Extra Instructional Time

The core problem of teaching a lower-achieving group in a tracked setting is that you’re trying to meet the same academic standards in the same amount of time, so the options are either to lower standards and teach a watered-down curriculum, or try to keep standards high but there’s not really a point to tracking.

One solution is to add instructional time. You can do this with or without tracking. Take all the students who are significantly below grade level in their math skills and give them an extra math class or an extended math class. This time is hard to use well. In some schools, students are put on some garbage computer program that claims to meet them at their level and that extra time is wasted. But done thoughtfully, and coordinated with the grade-level work students are doing, this can be valuable time to work on prerequisite skills, increase confidence, and give students some individual support.

Acceleration

Acceleration means having a student skip a grade level or course. It can happen by skipping a grade entirely, or be limited to one or a few classes. Acceleration can be great! For some students it's an easy way to find more challenges. It's not the best solution for every situation, and the logistics can be challenging. I've seen bright students who get straight A's accelerate in one subject and get a C the next year. Social factors can be challenging, as students are no longer with their friends and can be intimidated by being around older students. The reality is that acceleration is a blunt instrument. You either accelerate or you don't, and there are plenty of kids who are bored in class but wouldn't be served well by acceleration. Still, I think in lots of schools acceleration is underused, and logistical challenges are worth trying to solve.

Cohort-Based Acceleration

One of the challenges of acceleration is that it can be a lonely road. The alternative is to pick one year and have a large group of students accelerate together. This usually looks like taking Algebra I in 8th grade. As San Francisco learned, this is incredibly popular with parents. Accelerating in a cohort scales much better than individual acceleration, and many students benefit from the social support. The challenges with this type of acceleration are figuring out who is included, and making sure not to ignore all of the students in other grades.

Computer-Based Individualization

There are a ton of computer programs that claim to teach students at their level. Laurence Holt gave the definitive treatment for this approach in his article “The 5 Percent Problem.” The short version is that when students use these programs as they are intended, they can work well. But in most studies, only around 5% of students do so. Most students just aren’t very motivated to learn math on their own. With the current landscape this isn’t a solution that will scale to a large fraction of students. What computer-based individualization can do well is to support acceleration — helping students to fill in gaps to smooth the acceleration process. The other piece I think schools should consider is using computer-based individualization for a very small number of exceptional students. Most students aren’t motivated to learn on their own, but some are. I think this should be done really carefully. There’s a risk that kids just want to play computer games, or that parents hear about it and demand their child is included even if they aren’t a good fit. But online learning can be great for students whose number one priority is to move through the curriculum quickly.

The Point

Here’s the point of this post. Tracking isn’t necessarily good or bad. If it’s done well it can be a good thing. If it’s done lazily it can be bad. I find most arguments about tracking vs detracking to be pretty boring and simplistic.

My list above isn’t exhaustive. There are other ways a school can modify or supplement a typical tracking program. And that’s really my point. If the conversation is just about tracking vs not tracking, all of that complexity gets swept under the rug. If you’re going to track, do your best to do it well. If you don’t track, there are still a number of options available to support students who have different levels of knowledge and skills.

I also don’t think that tracking is ever going to live up to the expectations some people have for it. The shape of the bell curve is just too challenging to overcome. However, there is one more approach I think is worth considering. All of the approaches I described above can be implemented by regular schools with regular resources. This one takes a much larger allocation of resources, but if schools are serious about meeting students where they are I think it’s worth trying.

Curriculum-Based Grouping

Here's how it works. You start with a curriculum. The curriculum lays out the broad sequence of what we want students to learn. Then, you use assessments (ideally designed in conjunction with the curriculum) to figure out where in that sequence each student sits. Based on these assessments, you group students and place them at the exact spot in the curriculum that seems at the edge of what they know and don't know.

This is different than typical assessment, which either tries to say "this student is on a 7th grade level" or "this student has met the expectations for what we want them to learn in 7th grade." It's more granular. It says, "ok in 4th grade we expect students to learn A, then B, then C, and so on. Do they know A? Ok what about B?" And so on. Then you place a student based on that assessment at A or B or C or Q.

Placement isn't an exact science. Some students will know all of A, nothing about B, a little bit of C, and a lot of D. You do your best to place them, and then you reassess often and regroup students. So maybe you place that student at B, and they do really well and when you reassess them they're ready to skip ahead a bit.

It's hard to make even groups if you limit yourself to grouping within each grade level. You'll end up with the bell curve problem from before: there will be plenty of students around average, but a wide range in the tails. The solution here is to ignore grade levels when making groups. All of the students who know A and not B in the 7th grade curriculum will be placed to begin learning B, whether they are in 6th grade, 7th grade, 8th grade, etc. These might need to be modified within reason to avoid mixing students who are too far apart in age, but this type of grouping gives enough flexibility to do a much better job of helping each student learn on their level than any typical tracking approach.

The core problem of tracking is the bell curve. If a school sticks with grade levels as the foundation of groups, the tails of the bell curve will always cause problems. Curriculum-based grouping solves that problem by throwing away grade levels entirely.

Curriculum-based grouping is very rare in the US. It does exist — one prominent example is in Steubenville, where Emily Hanford profiled the success of the district’s early literacy program. But there are only a few commercial curricula that are designed for curriculum-based grouping.

I know I have a lot of readers who are big fans of the Direct Instruction programs, which use curriculum-based grouping. Why am I not advocating for more schools to adopt Direct Instruction? Here’s where I’ll make some of you mad. There is simply no universe where Direct Instruction becomes widespread in US education. The name and scripted format alone are disqualifying for most districts. Direct Instruction does a lot of interesting things, and a new program could learn some of those lessons and offer something genuinely new and exciting in the curriculum world. I would love to see an established curriculum company put together a new program with curriculum-based grouping. Schools would have to be willing to put aside the dogma of high expectations. But I think that’s possible. Many schools have spent huge sums of money and dedicated a ton of instructional time to personalized education software. There’s clearly a recognition that differentiation isn’t enough, that we should do more to meet kids where they are. But it’s also obvious to many teachers that education software hasn’t lived up to the hype. Is it time for a different approach to meeting students where they are?

A Final Thought

I don’t have many policymakers reading my blog. This post won’t make a difference in the nationwide debate about tracking. I do think it’s an interesting exercise in something that bugs me about education conversations. Teaching is an empirical science. There are lots of ideas in education that sound great from a distance. The TED talk and the splashy article in the newspaper make it sound obvious that Idea X will help students learn more. Then you try Idea X in an actual school with actual students and it’s a disaster. There’s no substitute for experience.

Tracking is one of those ideas that’s easy to oversimplify from a distance. It’s easy to come in and proclaim that your new plan will solve racism, or help every kid learn at their level, or whatever. But there are a ton of little details that matter. That’s the type of stuff teachers deal with all the time: some consultant or administrator comes in with a highfalutin idea that sounds great, leaves the details as an exercise to the reader, and teachers are left to pick up the pieces.

For instance, I work in a very small district. We don't have much tracking in high school. But we also have a partnership with the local community college to offer free classes for students. Almost all students take some classes at the community college, whether it's welding or English composition. Some students graduate from high school with an associate's degree. That's just one example of how the high school landscape is more varied than lower levels, because tracking is possible but it’s also possible for different groups of students to take completely different classes.

For statistics nerds, the spread of academic achievement isn’t necessarily a perfect normal distribution but the basic argument holds for any roughly bell-curve-shaped distribution.

The logistics of making school schedules work are way harder than many people outside of schools realize. To give one brief example: due to some complex scheduling factors, at one point last year I had one 7th grade math class with 28 students, including four students who were relatively new to the country and spoke little English, and seven students on IEPs. At the same time, I had another 7th grade math class with 12 total students and no newcomers or IEPs. And the classes weren’t tracked. The imbalance was purely because of scheduling factors outside of math classes.

I appreciate this post and very much appreciate your recommendation at the end. One mild objection I have—as one of the people who’s been most vocal about the value of ability grouping—is that it’s framed as sort of disagreeing with, sort of cautioning people who advocate for ability grouping, but “grouping doesn’t matter much if you don’t adapt curriculum to student level” and “the best grouping involves testing specific skills and then grouping based on those skills across grade levels” are two of the foundational points I and other grouping advocates raise.

Ultimately this is an objection to style much more than to substance. I see three important steps in terms of making the sort of grouping you outline happen:

1) recognition that ability grouping is valuable, overturning what has been a flawed consensus in the education ecosystem

2) having established that recognition, hammering home the best ways to group (which you outline) for people looking to move towards more ability grouping.

3) do the difficult structural work of building and testing those curricula and systems.

DI won’t scale everywhere? Sure, I don’t disagree. But something can (Telra is a good start!), and because this sort of grouping has been so out of focus, not a lot of people have been aiming towards building it. People need to recognize that it’s a goal worth aiming towards first, though, and that means—in my estimation—advocacy for ability grouping more generally. The whole shape of the conversation needs to change.

8th grade algebra is a good start, but it’s not the ideal for acceleration for the faster students so much as a floor. In a well-functioning system with curriculum-based grouping, I anticipate the top 5-10% at least will be ready for at least significant elements of algebra well before eighth grade.

I agree, tracking is a slippery slope and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. While it can help tailor instruction to student needs, it also risks reinforcing inequalities and limiting some students’ opportunities.

I taught middle school in an urban district, working with "at-risk" students who were below proficient in math and reading, many of whom faced behavioral challenges. With federal funding, we hired a math tutor who co-taught with the 7th grade teacher and worked with me too. All students received two periods of math instruction daily, with both educators providing various levels of support and intervention. We allowed students to essentially track themselves daily by choosing whether to work independently, get homework help, or join reteaching and homework groups. Homework was closely monitored to ensure understanding. Students with less than a C were required to attend an additional intervention during lunch for extra help, while others could attend optionally.

My students were with me from 6th through 8th grade, receiving the same interventions in 7th and 8th grade, with two daily math class periods providing both core instruction and targeted support, and a lunch bunch option. This consistent approach helped 75% of students pass the 8th grade math proficiency test, with significant growth shown by all.