Structure, Routines, Accountability

On the challenges of technology

A Story

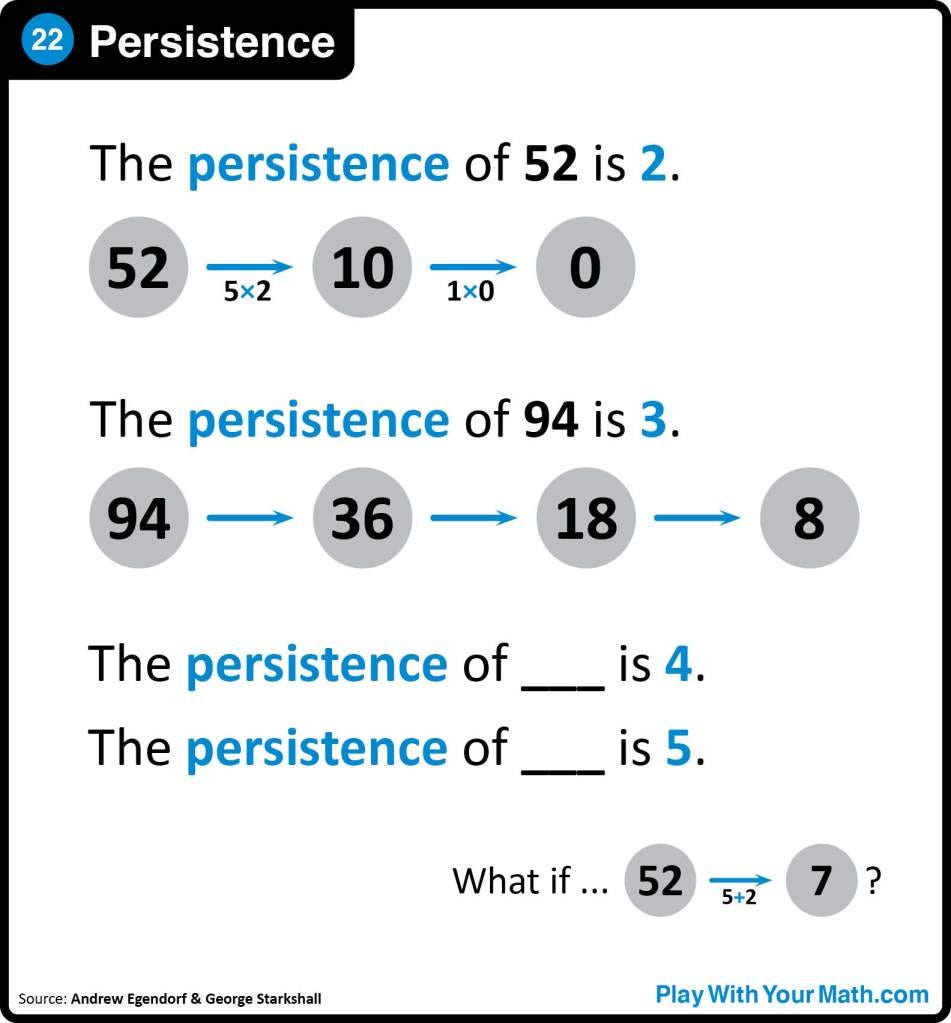

I have a challenge assignment each week for my students. It's optional, something they can work on if they're finished with an assignment early. It's always posted on Google Classroom to save time printing and copying. One week the challenge assignment was this problem from Play With Your Math:

One student had finished our quiz early. She was a bright and motivated student — she ended up taking a year of math online over the summer to accelerate in high school. I suggested she look at the challenge assignment. I was wandering the room but kept an eye on her as she opened up the link. She read the problem and, without missing a beat, googled "number with persistence of 4." The answer showed up (I won't spoil it here if you want to play with the problem), she typed it in, and moved on.

Two things strike me about this story. First was how casual she was. She googled the answer without thinking twice, as if she did this all the time. As if there was no purpose in the problem I had posed besides finding an answer and moving on while doing as little thinking as possible. And second, this was one of my more motivated students. If she was googling the answer, what was everyone else doing?

That moment happened three years ago. I'm a bit less naive now. I put a lot more structure in place for my students. I also use internet-connected devices a lot less. And still, I see this type of instinctive googling, instinctive avoidance of thinking, all the time.

Here’s a truth we don’t like to admit: if we put students on internet-connected devices, assign them some tasks, and don’t monitor what they’re doing, most kids will google or ChatGPT the answers. This isn’t a hypothetical. If you wander through some middle school and high school classrooms at a typical school, that’s exactly what you will see. It’s often under the guise of “ownership” or “independence” or “critical thinking.” It’s not every kid cheating, but it’s far too many.

Learning Things Is Good

I'll put a very brief stake in the ground here. I think learning things is good. Math is worth learning. So are lots of other things. I know we have little computers in our pocket that can look up vast amounts of knowledge in seconds. That doesn't mean knowledge is bad. Knowledge is what we think with, and we can only think with knowledge that's in our minds. Maybe I'll write a longer post sometime defending knowing things. If you disagree, feel free to stop reading.

A Headline

That story about my student googling answers came to mind when I saw this headline in New York Magazine:

This is news? Of course they're cheating their way through college. They're already cheating their way through high school. In some tech-heavy places they're cheating their way through middle school.1

There's another truth we don't like to admit in education. We like to think education is about inspiring students, about developing curiosity and an innate love of learning. School should absolutely try to do those things. But the elements of school that drive most learning are more pedestrian. Structure. Routines. Accountability. Structure breaks the complex task of learning down into lots of little manageable chunks that build toward larger goals. Routines get students into positive habits. Accountability communicates that we care about student learning, and we will intervene if students aren’t learning. Those are the drivers of most learning that happens in schools. They're also the solution to lots of challenges in education. Every student has a phone in their pocket? Let's give them some structure, routines, and accountability.2

The Goal

The goal of school is to get students to think. Thinking is what causes learning. There are lots of shortcuts to avoid thinking. Those shortcuts are tempting. They're tempting for everyone. Lots of adults struggle to learn things because they don’t have the structure, routines, and accountability they need to stick with a topic long enough to make progress.

Structure, routines, and accountability aren't hip or progressive. But when it comes to AI, they are the answer. Provide more structure. Don't just say, "write me an essay." Break that assignment into pieces. Handwrite some of them. Engineer more routines. Only use technology at specific times, for specific purposes. Practice what students should do when they’re stuck. Increase accountability. We care about your learning. Because we care about your learning, we are making some changes to make sure you are learning and not outsourcing your thinking to the internet.

None of that is easy. It’s a lot of work for teachers. It’s definitely easier for me as a math teacher, but even in math you might be surprised how often students will google answers without structure, routines, and accountability. It’s also not in the DNA of universities, and I’m not optimistic they will change to adapt to the moment. The specifics are tricky — they will depend on your resources, knowledge, and preferences.

But stepping back, there are some broad ideas I wish we all agreed on:

The purpose of school is to get students to think. Thinking is what causes learning.

Googling and ChatGPT-ing answers is a way to avoid thinking.

Far too many students will avoid thinking if we don’t take steps to stop them.

The best ways to get students to think are structure, routines, and accountability.

There’s no easy answer for what your structure, routines, and accountability should look like. They’ll work best if you collaborate with the teachers around you. It will take time and effort and trial and error. But the results are worth it.

I’ll qualify this with a reminder that not all students are cheating. Not all students are googling the answers whenever they’re unsupervised. But the goal of school is to educate all students, and far too many are cheating.

My school is finally (finally!) banning cell phones next year. We had a meeting two weeks ago to hash out the structure, routines, and accountability. It will be a lot of work at first. I’m excited, it will make a huge difference for us.

I think this essay echoes and underlines the first standard of the Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice - "Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them." But I think that generally speaking, persevering and not taking advantage of the available instant gratification has become harder and harder in our lives as a whole, not just in the (math) classroom. Instead of solving the problem on your own, you can google the answer. Instead of walking or taking the bus, you can call an Uber. Instead of cooking or shopping, you can tap on your phone an order from DoorDash or Instacart. etc. etc. And because the costs of so many of our "real-life" short cuts are virtual - payments done online and not in physical cash - it's hard to see its impacts in a visceral way.

That being said, I often wonder how to justify the stance that "learning things is good" to students (and to my own children). I'm not a fan of "because I said so" justifications, which then spins me down a rabbit hole of... *Why* is it important to "learn" things on your own, if you can just "know" them by looking up the facts/answers/tutorials online? What does it mean to "learn"? Is it necessary that "learning" happen off-line? What does it mean for something to be "good"? Is it "good" because it will help us later? That line of reasoning feels like it echoes math teachers who teach algorithms to students without any sort of rhyme or reason, except for that the students will "need it later." So then I kind of get myself all up in a tizzy. (To be fair, I was a math and philosophy major so I'm probably prone to overthinking... ahahah)

Unfortunately, getting people to think (or develop skills or acquire knowledge) is not really the primary goal of education. There are many other competing goals, including 1) keeping kids in a safe environment so that parents are free to work 2) ranking kids 3) building character in various forms 4) helping kids socialize appropriately. For example, if you told all your parents that their kids were going to think more, but it would require the school day to be two hours shorter, the parents would absolutely refuse.

Anyway, I'm not disagreeing with your main arguments -- I agree that thinking is good, and so are structures and routines -- I just don't think all of the stakeholders are aligned in their goals (despite what they say), and that's why parents/administrators/students do not always support reasonable courses of action.