Progress Monitoring

How I monitor student progress, and a rant about how not to monitor progress.

This is a long post so I’m going to put the thesis up front:

It’s popular to use digital “interim assessments” that find the “grade level” a student is at in math class. The tools schools use for this often aren’t very accurate, and that information can feel overwhelming and isn’t actionable for teachers. Instead, pick some specific skills that students need to be successful with grade-level content. Assess those skills and prioritize the skills where students need the most work. Then assess again to see how it’s going. Figure out which skills need more work and which students aren’t making progress and act on that.

In the last few years, at least in the US, more and more schools are collecting data in an effort to monitor progress and figure out whether students are learning. It's a good idea in principle but I think the tools that many schools use for this type of progress monitoring are garbage. This post is a rant about what I don't like and a description of what I do instead.

What does effective data collection for progress monitoring look like? I think there are two key pieces: data should be valid and actionable. If it's not valid it's not useful, and can end up leading teachers in the wrong direction. If it's not actionable teachers end up overwhelmed by the challenge of teaching students who are “behind grade level,” or just unsure what to do with the data.

A Rant

What lots of schools use right now is some sort of computer-adaptive test that purports to tell teachers students' grade level or percentile rank. They are often called “interim assessments.” A few popular ones are NWEA, i-Ready, ANet, and IXL, though there are plenty more.1 The logic goes something like this: Any classroom has a wide range of math skills. If we can figure out a student's true grade level we can personalize their learning or teach better or something.

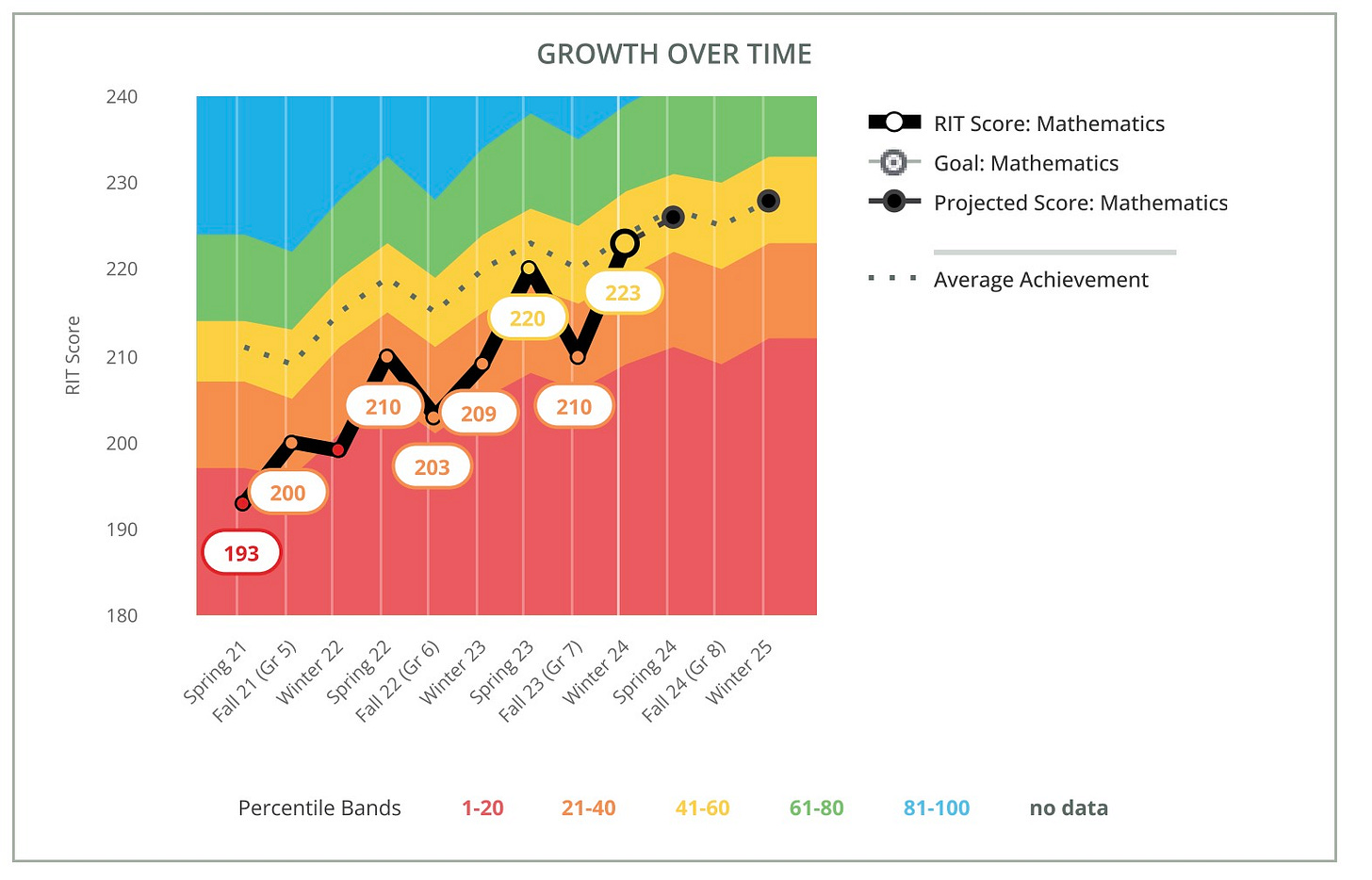

The thing is, these tools aren't very accurate. Here is an example of a handy graph that NWEA spits out. The colored bands are quintiles, so 0-20th percentile, 20th-40th, etc.

That's a typical student. Not someone who is guessing wildly each time, just regular effort on the test. Most students’ scores bounce around like this. The test gives me some information — this student is generally making progress and is probably somewhere between the 30th and the 50th percentile. NWEA has a handy table for converting that to a grade level. But I don't have a very precise idea of where their skills are. Lots of schools use this information to do ability grouping but the reality is that student could be anywhere in a pretty broad range. Despite students taking this hour long, expensive, computer-adaptive test, I don’t have an accurate indicator of their overall skills. Most tests give breakdowns for different subdomains like fractions or geometry but those results are even less accurate. The reality is that math skills don't exist on a neat continuum where we can put a number on a student and summarize everything we need to know to teach them. These numbers bounce around because tests are imperfect, and also because the underlying construct doesn't really exist. A student might be good at solving equations when they can use mental math but struggle with trickier numbers. A student might be good at multiplying and dividing fractions but clueless with adding and subtracting. It's impossible to distill that down into a single number.

Even if these tests were accurate, what would teachers do with that information? How does it help a 7th grade teacher to tell them that half their students are at a 5th grade level or below? Should I teach 5th grade standards instead? It feels overwhelming to see data like that and there aren't very many clear action steps I can take to respond. Some tools recommend specific skills for students to practice but they often end up practicing random skills I don't care about. Would I like my 7th grade students to get better at decimal arithmetic? Sure. But decimal arithmetic is pretty low on my list of priorities. In 7th grade we almost always use calculators for decimal operations. I'd rather have students working on more relevant skills like fraction multiplication and division. These digital tools don’t set clear priorities and students end up working on random stuff that’s not very important.

The idea that we need to identify a student’s grade level in math is often followed by a desire to have them work “on their level,” usually on some expensive online program. The reality is that if a student is two years “behind” in math, it’s not realistic for them to magically learn two years of math while sitting on a computer for 30 minutes a day. I’d much rather prioritize a few key skills and focus on those while giving students more support with grade-level content. Of course these tools want to make it look like they are helping students. NWEA is refreshingly transparent with their data. Other tools make it look like a kid is making progress because they got a couple questions right on a skill, marked that skill as “mastered,” and moved on. There’s no spiraled practice, the kid forgets what they “learned,” but the website tells the teacher the student is learning and we can all look the other way and pretend everything is ok.2

These tests corrupt learning in other ways. Lots of schools become obsessed with the test, giving kids ice cream parties if they show growth and having assemblies to convince kids to try their best. It's as if schools think that trying hard on a test causes students to have learned more over the preceding months. Since the tests aren't very accurate, plenty of kids who have been working hard in school get excluded from those ice cream parties. The message is clear: you worked hard but hard work doesn't always pay off. With kids taking some of these tests multiple times a year almost everyone will get excluded at some point. If you wanted to design a system that made kids less motivated on standardized tests it would look a lot like what many schools do with these assessments.3

What should we do instead?

My job is to teach 7th grade math. I will always have students who lack skills they should have learned in previous grades. There's a lot of math I could try to reteach. The best thing I can do is to focus on the most important skills students need for 7th grade. At the start of the year I design an assessment of the foundational skills kids need to be successful in 7th grade math. It’s a bunch of quick questions on specific skills. Multiplying and dividing fractions, one-step equations, some other fraction operations, a few other whole-number skills. I break skills down into pieces, so one question each on one-step equations with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Multiplying a whole number by a unit fraction, multiplying two fractions. Etc. I have students do it on a Chromebook so it's auto-graded and easy to analyze the data.

Once I do that, I have a list of the skills students need to know to be successful with grade-level math and my students' performance on each skill. Teachers will always say, "I don't have time to reteach everything." Well don't reteach everything. Use an assessment like this to prioritize. For instance, most of my students did well with addition and multiplication equations, but subtraction and division equations were a mess. Now I know — we could use a bit of review on addition and multiplication, but I should focus most of my energy on subtraction and division. Multiplying fractions was ok but dividing fractions was a big weakness. Great, that helps me prioritize.

Then I reteach a bunch of skills that students need help with. And importantly, I don't start the year by doing a month of review. I reteach skills here and there when I have ten minutes for a mini-lesson, ideally right before they come up in the curriculum. I build in spaced practice for those skills each week. For instance, I think rounding is an important skill, and students didn't do very well on my assessment. I did a few mini-lessons reteaching how to round right before our unit on circles and mixed in a bit of practice. Multiplying by pi during the circles unit gives students lots of chances to practice their rounding skills and helps those mini-lessons stick.

Every few months I assess again. Here I'm looking for two things. First, which skills have students made progress on? Are they doing better with subtraction equations or do we need to do more practice? Second, which students are making progress? They aren't likely to go from 20% to 100%, but if they're moving in the right direction that's a good thing. If a student isn't making progress on these foundational skills, why not? How are they doing with grade-level content? What other interventions can I put in place? It's not manageable to learn that half of your students are at a 5th grade level or below and be told you should be providing personalized instruction for all of them. It is manageable to pick some specific skills, reteach them, see which students are making progress, and prioritize additional interventions for students who are not.

One more thing I like about this system is that it prioritizes full-class instruction first. In the age of technology I think teachers are often too quick to divide students up and have them do different stuff on a computer. A ten-minute mini lesson on a foundational skill is useful for everyone. The goal of intervention should be to do as much as possible with full-class instruction before resorting to individual intervention or separating students.

I said before that an effective system should be valid and actionable. This does both of those things. Rather than trying to put a single number on all the math students have learned, I'm getting more specific information — what percent of my students can round to a whole number? What percent can divide fractions? Who has made progress with the skills I’ve been teaching and who has not? Those numbers have a clear meaning to me. Seeing that half of students are on a 5th grade level is overwhelming. Seeing that I should focus on subtraction equations and fraction division first feels like something we can do. The assessment gives me clear action steps. I have limited time, so I can focus on the skills students need the most and track progress on those skills. Then, I can see which students aren't making progress and need more support.

This system isn't perfect. No system is. It can be hard to know how far back I need to go when reteaching a skill. It can feel overwhelming to look at how many students aren’t making as much progress as I want to se. But I think this system is leaps and bounds better than how most of interim assessments are used and it takes a fraction of the time.

A Final Thought

I’m sure there are teachers reading this saying that all sounds nice but I just don’t have the time. I understand that. Start small. Pick ten foundational skills for your grade-level content. Make a digital ten-question quiz on those skills. Give it to students, and use it to pick two or three topics to prioritize. I like this system because it can scale to match the time I have. If you have more time, reteach more skills. If you’re squeezed, trim it down and do what you can.

I’m not talking about state standardized tests here. I would do some things differently if I was in charge but I understand the value of taking a few days a year to see how students are doing on these tests. I’m talking about assessments that schools pay for and give to students in addition to state standardized tests.

Fun fact — EdReports tried to do a series of reviews of the major interim assessment publishers. Almost all publishers either refused to participate or refused to share enough information for a meaningful review. Doesn’t exactly inspire confidence in these things. You can read about that here.

There are some legitimate uses for these tests. It is always hard to pick out the signal from the noise but with multiple data points it’s possible to use these tests to see which students aren’t making progress year after year and target interventions. I could also imagine these types of tools shedding light on whether a new curriculum is working or something like that. I’m most familiar with NWEA and IXL, maybe other tools do a better job. The core problem is that school and district leaders are obsessed with buying things that find students’ “grade level” and that drives the whole paradigm. The tests are used poorly far more often than they are used well and they take valuable instructional time away from teachers without providing valid and actionable data.

I like how you pointed out the positives of interim tests at the end as I do see them having some value but totally get your point on "they don't really tell a teacher anything". I think the way I think about it is that those tests are merely one data point that overlayed with the right granular data, could be supportive. That's actually something I am trying to work on right now and would love your feedback. I am also curious if you think there's a good resource out there (besides achieve the core website) that helps teachers figure out those ten "foundational skills" they should assess at the beginning of the year.

“Lots of schools use this information to do ability grouping but the reality is that student could be anywhere in a pretty broad range.” This is a good reason that schools should move away from ability grouping and tracking. Even when triangulated with other assessments, the result is usually a bunch of “low” kids not receiving grade-level content.