High Accountability Teaching

All the little nudges that motivate students to learn

Here’s a sentiment that’s pretty common to hear from teachers:

The sentiment is, you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink. Teachers teach, but we can’t force the student to learn. If they choose not to learn, that’s up to them.

“She didn’t do anything for her essay. She’s going to find out how much a 0 affects her grade.”

“I’ve given him every resource he needs. If he doesn’t open the book, there’s nothing more I can do.”

High Accountability Teaching

I try to teach in a very different way. It’s what I call “high accountability teaching.” The message is: you are here to learn, I care about your learning, and I expect you to participate and do your part to learn.

I think this is a real dividing line between teachers. Some teachers say it’s their job to teach, and students can choose whether they want to learn. Others say they will do everything in their power to make sure every student learns.

A Mental Model

Before getting into some of the nitty gritty of this type of teaching, we need a mental model. Credit to Adam Boxer, from whom I learned this mental model.

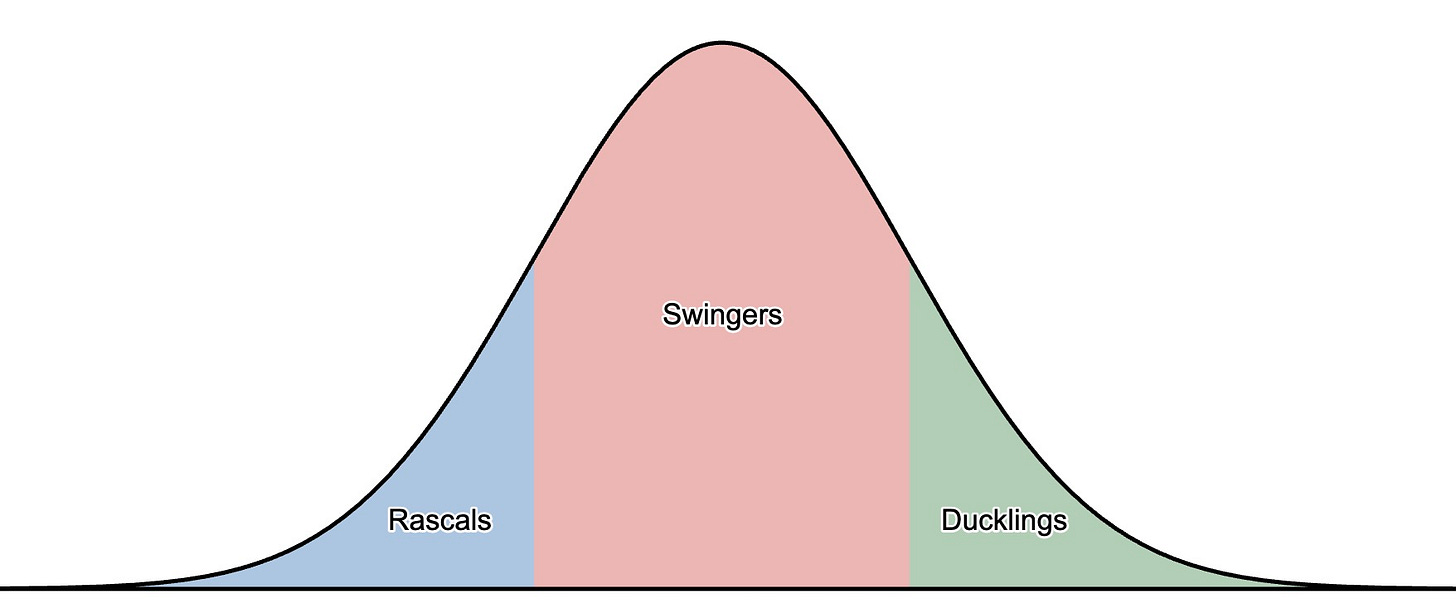

In any group of students, motivation to learn will fall on a bell curve. We can roughly divide that bell curve into three groups.

On the right are “ducklings.” Ducklings will generally do what you ask. They don’t particularly need high accountability teaching. They’re the students every teacher wants to have.

On the left are “rascals.” Rascals will test boundaries, challenge the teacher, and generally see what they can get away with.

In the middle — the largest group — are “swingers.” (Lol, blame Adam, his word not mine.) Swingers can go either way. They tend to follow the crowd. If everyone else has their nose to the grindstone working hard, they will get to work. If everyone else is diligently paying attention, they will follow suit. And if everyone else is goofing off, they will happily join in. 1

The core of high accountability teaching is to get as many of the swingers on board as possible.

There will always be a few rascals. It’s absolutely possible to get rascals motivated and learning. But motivating rascals takes a lot of individual effort and relationship-building. If I’m playing whack-a-mole because the swingers are causing a ruckus, I’ll never have the time and energy to motivate the rascals. If I can get some momentum with the swingers, I can focus my efforts on the final few students who need individual attention.

Also, rascalhood is relative. If a bunch of other students are stealing pencils and having a chat instead of doing math, rascals will up the ante and throw a calculator at someone’s head across the room. If the rest of the class is focused, rascals will push boundaries by humming when I ask them to work quietly, or sneaking cheez-its in their sweatshirt pocket and eating them while I’m not looking.

The Teacher Moves

What does a high-accountability classroom look like? It’s really the sum of dozens of little teacher moves. They won’t all fit in this post, but I’ll outline a bunch of my favorites.

Be seen looking. This is my number one, a teaching fundamental that I find absolutely essential. When I ask students to do something — try a few math problems, put their whiteboards away, turn and talk with a partner — I stand and actively scan the room, looking to make sure students follow through. My goal isn’t to catch students doing the wrong thing. In fact, if Jimmy doesn’t get started, I avoid saying, “Get to work Jimmy,” because that signals to the entire class that Jimmy isn’t working. Instead, my goal is to use eye contact, proximity, and gestures to get as many students following directions as I can. One classic behavior of swingers is that, when I ask the class to do something, they will look around the room to see if everyone else is doing it. I often make eye contact with those students and communicate with my facial expression that I meant what I said. The goal of “be seen looking” is to communicate with body language that I am serious, that yes I expect everyone needs to try these problems, and I am following through to make sure that happens. It’s helpful to contrast with two non-examples. Don’t say, “here are some problems for you to try,” and go sit at your desk. That communicates that you don’t care whether students try them. And don’t ask students to get started, then immediately start running around the room helping students. Those swingers are looking around to see if everyone else is working, and you’re missing an opportunity to nudge them in the right direction.

Be quick, be quiet, be gone. Ok so Jimmy still isn’t getting to work. I avoid calling Jimmy out in a way that brings attention to him. Instead, my goal is to quickly and quietly stop by his desk and give him an extra prompt. Then, I walk away. That last piece is important: I don’t stand over him waiting for him to start. That’s a recipe for a power struggle. Instead, I give him a minute, and follow up again if he doesn’t do his part.

On-ramps. Often, swingers swing toward low effort or disruption because they aren’t sure what to do. As often as I can, I start an activity or sequence of questions with something I know students can answer. This acts as an on-ramp, to get students started and building confidence with independent work. Does this always work perfectly, or guarantee that students are suddenly perfect little mathematicians? No. But that positive momentum to start an activity makes a huge difference in the collective feeling of motivation and effort in the room.

Habits and routines. I have a ton of routines I use literally every day. When students walk into class, it’s always a Do Now with the same structure and format. I have routines for quick chunks of independent work, for mini whiteboards, and more. Every routine is a chance for students to build positive habits. Those habits become automatic, and spread to the vast majority of students.

Seating. There’s a common teaching strategy where you take the rascals and the swingers with the worst behavior and you stick them in the back of the room. It’s a kind of detente: I’ll put you in the back of the room and let you cruise by without putting in much effort, and you’ll be a bit less disruptive to the students who are here to learn. Don’t do this. Stick them up front. This takes some courage, but the message is clear: I care about every student’s learning. Seating rascals up front is tough. And sure, there might be occasional exceptions. But in my experience, the vast majority of kids who a teacher sticks in the back of the room to minimize disruption are capable of learning if we set them up for success and hold them accountable. This probably isn’t something to try all at once, to completely upend your seating chart and expect learning to skyrocket moments later. But the detente of putting students in the back and ignoring them is contagious. You can’t have a high accountability classroom without making these types of decisions around seating.

Academic support. All of those strategies above are little nudges to push students toward higher effort in class. But often, the reason students aren’t motivated is that they are lacking some skills. Those nudges don’t do much good if students put in effort but constantly feel dumb and can’t keep up with the class. When a student seems unmotivated, I will do my best to find some time to work with them one-on-one. I use this time to shore up relevant foundational skills, and maybe pre-teach an upcoming topic. I have limited time for this type of one-on-one work, so I can’t do this for everyone and I can’t always do it consistently. But even occasional one-on-one support can make a big difference because it sends the same message as the rest of these teacher moves — I care about your learning and I know you can do this.

Cautious with extrinsic incentives. I avoid giving students rewards for effort in math class. Most extrinsic incentives are helpful in the short term but can be harmful in the long term. I am generous with praise, and I try to recognize effort, growth, and high-quality work each class. The best long-term motivation strategy is for students to feel accomplished when they know they’ve put in the effort to learn something. That doesn’t always work, but I resist the urge to use bribes and short-term rewards to compensate.

Connect consequences with behavior. In many schools, and for many students, consequences become a kind of game. Detention isn’t so bad, all my friends are there, so I might as well wander the halls rather than going to class. What was the detention for? Who knows. The most effective consequences are tied directly to the behavior we want to change. Your mileage will vary, every school has different systems. But one tool I’ve found helpful is that if students aren’t putting in effort in class, I’ll have them come in for the first few minutes of lunch and we’ll work on the task together. Students don’t like this very much, which is the point. But it’s short, typically under 5 minutes, and it’s focused on the specific academic tasks they weren’t doing in class. And they get some extra help, so I can figure out if there’s some extra support or missing skills I need to address. This exact thing might not work for you. The point is, if I’m going to give a consequence, I want it to be clearly tied to the behavior I’m hoping to change.

And many more. I could go on for a while. Giving clear directions. Keeping transitions tight and efficient. Using whole-class response systems so every student is engaged and answering questions. Getting routines right from the start of the year. Contacting home for persistent issues. There’s no one magic bullet. But you add up all these teacher moves, and over time they can make a big difference.

There’s a logical mistake you can make when thinking about motivation. There will always be some intransigent rascals who are tough to motivate. You can try all sorts of nudges to get them learning and fall short. The logical mistake is to focus on those students, and forget that for the large majority of students, small nudges can add up to a big difference. That’s where the mental model of ducklings, rascals, and swingers can be helpful. Sure, these teacher moves don’t work for every student. That’s normal. But they do work for many students. Focus on that big group in the middle, get as many students as possible learning with whole-class teacher moves, and work with the rest on a case-by-case basis. If you can flip the momentum of the swingers, that leaves a lot more of your energy to support the rascals.2

Going It Alone Is Tough

If you are the only teacher trying to create a high accountability classroom in your school, you will have a hard time. All of this works way better if you are on a team where all of the teachers are using the same teacher moves and the same language, coordinating their interventions and multiplying each other’s work.

High accountability teaching isn’t much of a value at my school. I have some great colleagues, and there are absolutely some other teachers pushing accountability for students. But there’s not much common language for me to lean on, and it’s not a priority for the folks in charge.

It’s a tough place to be in. Some schools have a strong school culture, or have students who arrive with strong motivation and academic skills. Others don’t. You might read this post and think, “Wow, my students do all this stuff without me having to put in all that effort.” I’ve worked at schools like that! It’s nice.

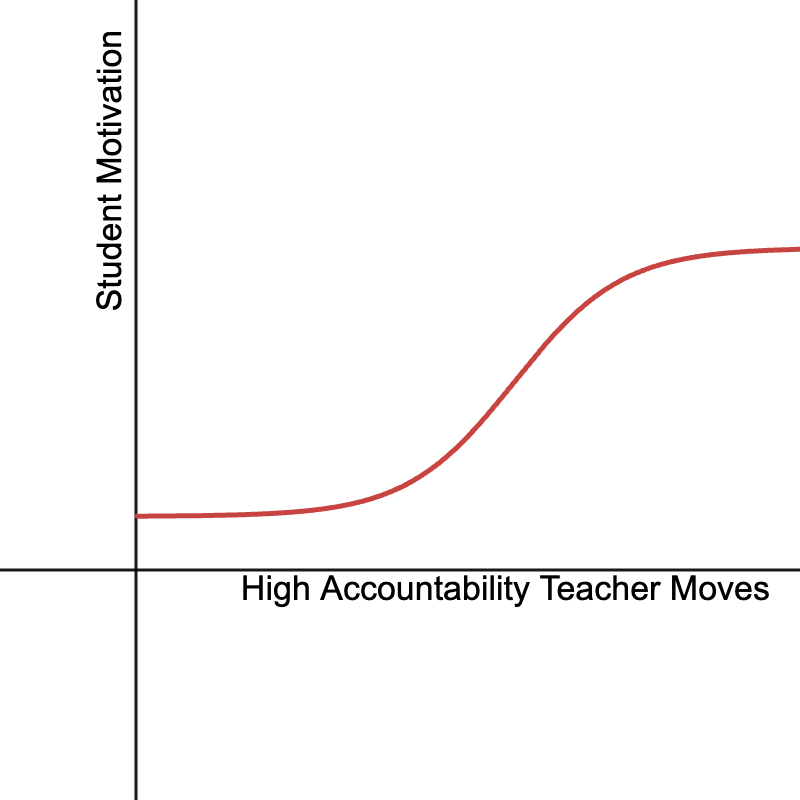

The toughest thing about working in a school like mine is that high accountability teaching is slow to impact motivation. It looks something like this:

Sure, you might be able to find a few teacher moves that make a difference in your classroom overnight. But my experience is that the vast majority of changes are slow and incremental.

One reason is because the swingers follow the crowd. It’s tough to move the needle when many of your students are playing follow-the-leader in the wrong direction. That doesn’t mean that your efforts are worthless, but it does mean you need to persist even if it feels like progress is excruciatingly slow.

I also think this idea can help us understand why motivation has felt like such a challenge for the last five years. Many teachers feel like they’re teaching in a totally different world than before the pandemic. Have students changed that radically? I don’t think so. But because swingers have such a strong influence on the culture of a classroom, a disruption to the system can cause a reset to a new equilibrium that feels very different from before.

A Final Thought

I totally understand why teachers choose to teach with less accountability. High accountability teaching is a lot of work, and if you’re on your own it can feel like rowing upstream without making any progress. I can’t promise any specific outcome in your classroom. Teaching is hard. But I can say that I have spent a lot of time trying to increase accountability in my classroom. For a while progress was slow. It felt like two steps forward and one step back. But eventually, things shifted. I reached a tipping point in my ability to get that big group of swingers on board. My classroom is in a much better place now. But only because I stuck with it. It’s a slow road, but all those nudges add up eventually.

I also think a lot of teachers have a misconception about accountability. Accountability can feel like we’re trying to catch students doing things wrong, or mete out consequences for bad behavior. That’s not it at all. The goal is to send the message, with everything that I do, that students are capable learners and I will follow through to make sure they are learning. I’m not following through because I want to get anyone in trouble. My goal is to help students build habits so they’re putting in effort without even thinking about it, because that’s what we do in math class, because that’s how we learn.

One response to this idea of ducklings, rascals, and swingers is that it seems to put students down or look at them in a negative light. I don’t feel that way at all. I think pushing boundaries is a perfectly normal and healthy thing for kids to do. Think about how humans evolved, in small groups of hunter-gatherers. In that context, it’s adaptive to have some individuals who are rule-followers, others who are constantly pushing boundaries, and a bunch in the middle who follow whatever seems to be the best idea at the time. It’s evolutionarily adaptive for some young people to push boundaries, and for there to be a range of responses to authority. I don’t think students are bad people for pushing boundaries. I also don’t think misbehavior or low motivation are inevitable. It’s the job of teachers to set boundaries and create a high accountability environment that nudges students to learn, even if they aren’t always predisposed to do so.

You could think of this post as a classroom management post if you like. That’s not how I’m choosing to frame it — I’m thinking in terms of accountability for learning and motivation for learning. I think that framing is helpful because classroom management conversations can devolve into a focus on controlling students and addressing misbehavior, without considering whether all that effort leads to any learning. My goal here is to prioritize the classroom management moves that maximize learning, and focus less on control.

Truly loved this and wish I had it when I first entered the classroom. It felt near impossible to find explicit teacher moves that were tied to "high expectations" teaching.

Also, I believe we would have different expectations of doctors if they had the same face time with patients as teachers do with their students.

"[Y]ou can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink."

Years ago, my dog was having some health problems that the vet attributed to insufficient water intake. I pointed out that we always kept a full water dish that our dog had constant access to and said something like the quote above. The vet looked at me like I was insane, or at least a bad dog-dad.

"Of course you can. First, you put some ice cubes in the water. If that doesn't work, you pour a little Gatorade in it. If that doesn't work, try chicken stock. She'll drink more if you change the water."

Ice didn't work, but Gatorade sure did. After a couple of days, we stopped adding Gatorade, and our dog's water intake stayed at its new, higher level.

That's stuck with me for about 15 years now. Kids aren't dogs, but sometimes a small change in the water is all we need. When I added on-ramps at the start of class that I knew kids would be able to answer, it made a huge difference in their cognitive engagement for the rest of the period. I figured that was the classroom equivalent of a little Gatorade.