Don't Talk to Me About the Factory Model of Education

And a bit of a rant about lazy thinking in education

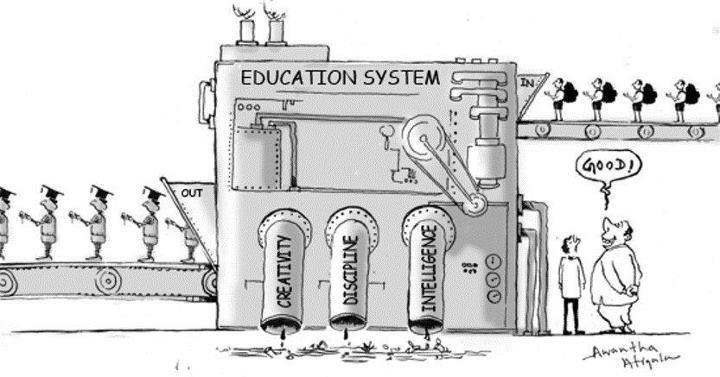

I hate when people bring up the factory model of education. Statements like, "The factory model of education treats students like products on an assembly line, prioritizing efficiency, standardization, and control over creativity, individuality, and deep learning." I hate it because it's often lazy rhetoric, meant to communicate "I know how to talk about education in this fancy way so I must be right." I hate it because it's a non-sequitur. Schools were founded on a factory model, therefore you should incorporate the four D's I just made up into your lesson plan or whatever. But I also hate it because it's wrong. Here are some fun facts about the factory model to pull out the next time a consultant starts talking about the factory model at your district PD.

Some History

The first large expansion of public education in the US was the common school movement of the early 1800s.1 The main goal of this movement was to strengthen the young country's democratic institutions, not to turn out efficient workers. In New England, where the first common schools proliferated, there was already a relatively high literacy rate for free males. But that education was disjointed, happening through apprenticeships, in the home, through private tutors, or informal collectives. The common school movement brought people of all classes together under one roof. The goal was to break down social barriers and instill a shared national identity and commitment to the common good. Horace Mann wasn't trying to efficiently create workers; he was trying to buttress the democratic institutions of a young nation. The Industrial Revolution was underway; the factory model could have been a major influence on the education system. But it wasn’t.

While there was a push for more standardized and efficient education in the 20th century, this push had as much to do with pressure from parents as it did any top-down desire to create factory-made docile workers. Many educational thought leaders emphasized educating the whole student and saw education as a force for democracy and the common good. Much of the desire to prepare students for the world of work came from parents, not a sinister plot by corporate leaders. As high school became universal, kids were spending more and more of their time in schools and families wanted to feel like that time was worth it. This is where things like age-graded classrooms, fixed schedules, and standard curricula became part of the education system. You can look at the modern American high school as a sort of grand compromise, trying to balance high-minded goals of the common good, practical realities of preparing students for their future careers, and the desire for upward social mobility.

There actually was an education model designed very much like a factory. It was called the "monitorial system." The basic premise is that students teach other students in an assembly line manner, supervised by a teacher in a large room. So Jimmy teaches Timmy multiplication facts. Then Timmy teaches Tommy multiplication facts. Then Tommy teaches Johnny multiplication facts. Meanwhile, Jimmy goes and gets taught division by someone higher up the assembly line, and the process continues. While one goal of the system was order and efficiency, another goal was to make education more inclusive by allowing more students to attend without having to hire large numbers of additional teachers. You can have whatever opinions you like about this system, but 1) it is mostly gone today, and 2) it doesn't fit neatly into the narratives people spin about the factory model of education.

Optimism

Part of the reason I find this interesting is that I'm an education optimist. While our system is far from perfect, I see those imperfections as products of the size and ambitious goals of today's schools. Schools are amazing places. Not in the sense that every moment of learning is amazing — they are deeply imperfect, and I know we fall short far too often. Stop by my second-period class if you'd like to see what falling short looks like. But schools are amazing in the size and ambition of the project we've taken on. My education optimism is that the basic model of school that we have today is good, and the best way we can improve it is to iterate within the structures we have, not to tear everything down.

Rhetoric about the factory model of education often suggests that the status quo is not only broken, but created by malign forces operating against students' best interests. That's not true, and it's also unproductive in trying to improve the systems we have. Schooling is incredibly complex. There are no shortcuts. There's no magic bullet. There’s no puppetmaster behind the scenes. There's slow, incremental progress. Or there's a slow decline, from bad ideas and lazy thinking. The evidence points mostly to decline right now, in the US, if we're being honest. And that makes it more tempting to look for an easy way out, for quick fixes or abrupt reinventions based on wishful thinking and naiveté.

Bold statements about the factory model are a symptom, but they're also a metaphor. Too many education leaders don't understand our history, struggle to grapple with complexity, and focus on superficial changes. I don't know if that will ever change. I hope it will, and I believe in our system. That’s my optimism. But in the meantime, I enjoy bursting peoples' bubbles about the factory model of education.

This post draws on David Labaree’s book Someone Has to Fail, which is an excellent high-level history of education in the US.

This is interesting to read, coming from an animal science and education backgrounds. I actually got into of education largely because of observed difference in public perception versus the reality of doing the work. A very clear and relevant example is there is no such thing as factory farming- farms churning out livestock by treating them all the same in the most minimal but effective way that not only negates the individual needs of each animal but also does it with as little human interaction as possible - implying a cold detached push of products through the system to maximize profits at the expense of everything else. That simply doesn't exist; there is a network of people working together to meet standardized mass production needs- sure- but its very much a hands on process that contains way more interaction and relationships between people and animals than the general person assumes.

Thing is -its infuriating, from an agricultural standpoint, to hear people lament about factory farms when they have zero idea what actually goes into producing their foods.

But the people complaining about the factory model of education have actually been through an education, and likely know someone currently going through the educational system. The problem isn't so much that schooling doesn't look like factory production in some way or another (because it really doesn't)- its that people come out of the system *feeling* like a product and like their education was simply something applied indiscriminately to everyone so they can be that product. The feeling of being churned out doesn't change with people's historic understanding of education, and is the far more important aspect of the term, in my opinion.

*the term factory here is ill-suited, as the goal of factories doesn't involve one-size-fits-all methodology and therefore turn all input into the same output; the goal is to find the most effective and efficient method for completing each step of the process, so the whole process comes together in the most efficient and effective way

It's so interesting and helpful to know about the history of education. It seems neglected. Do schools of education even cover it? Do education journalists and policymakers know it? If there was more familiarity, it might even stem the tide of tired tropes and the constant churn of old wine in new bottles. I've been reading Diane Ravitch, Lawrence Cremin, and Jonathan Zimmerman. I haven't read Labaree, so thanks for the recommendation. One thing I learned recently: It's not quite accurate to say the main goal of the Common Schools movement was to "strengthen the young country's democratic institutions". It was in large part motivated by the influx of Catholic immigrants and the desire to withhold state support for Catholic institutions. The first common schools had a clear Protestant orientation.