A Dose of AI Skepticism

Maybe that thing you thought is better isn't actually better

Teachers across the U.S. will start returning to work in the next few weeks. Maybe you'll return soon. And when you return, maybe you'll hear from a colleague about how you just have to try this AI tool. Or maybe it'll be a consultant telling you this is what you have to do to avoid being left behind. Here's a fun new piece of evidence to consider if that happens to you.

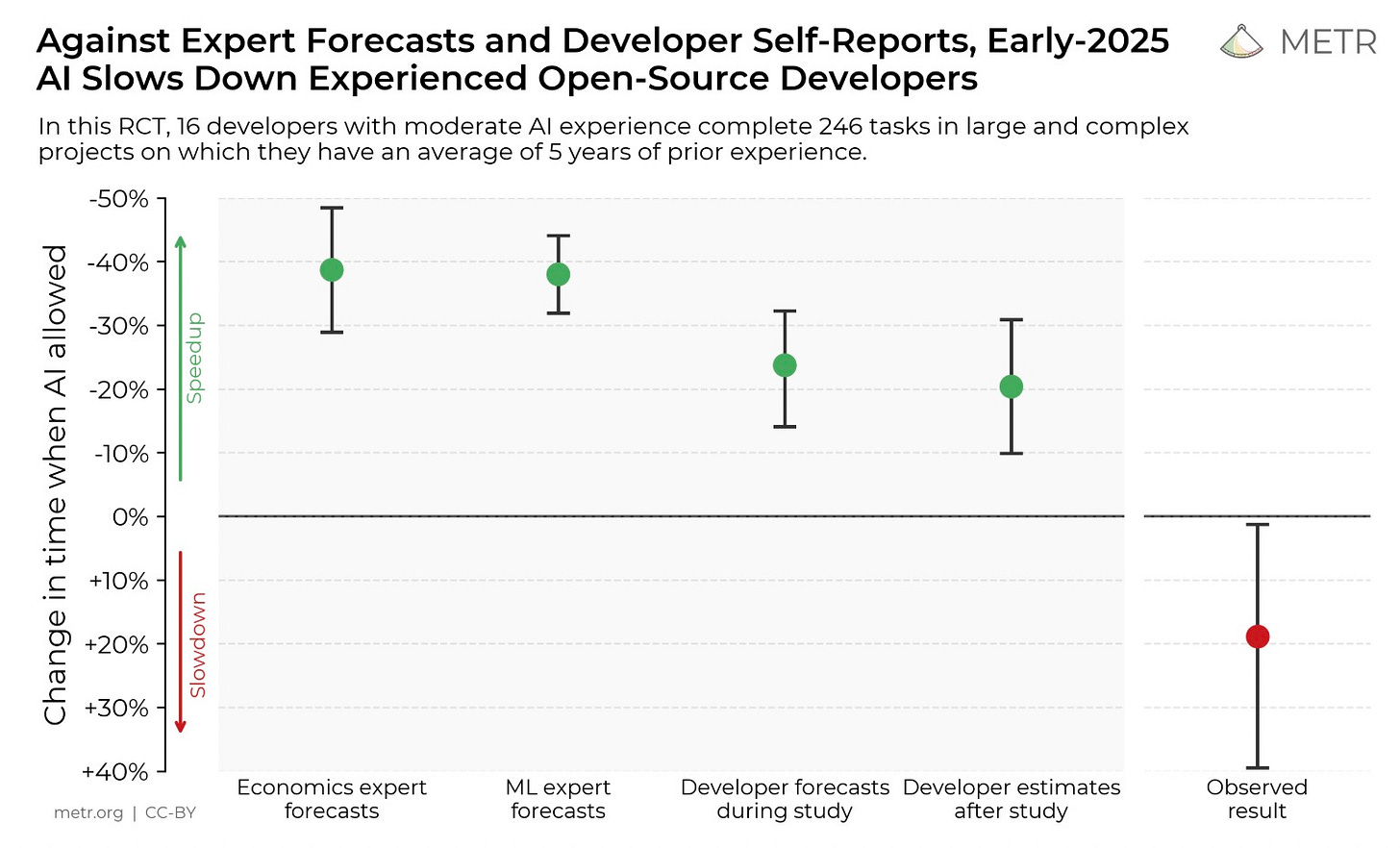

An organization called Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR) did a study on how AI helped coders with productivity. They recruited a bunch of experienced coders and had them prepare a list of real tasks they needed to complete, with an estimate of how long they thought each task would take. Each task was randomly assigned to be done either without AI, or with AI allowed.

Long story short: using AI slowed coders down. On average, they finished tasks faster when AI wasn't allowed. Probably not what you expected! File this under "maybe AI isn't changing the world as much as some people think." This is just one study and it has its limitations, though it's also rigorous experimental evidence. You can read a more thorough description here if you're interested.

But there's an important note about the study that's worth emphasizing, especially when that eager colleague of yours tells you how amazing AI has been planning their lessons or whatever. Coders completed tasks 19% slower (on average) when they were allowed to use AI. But the study also asked coders to self-evaluate whether they thought AI made them faster or slower. On average, when coders were using AI, they thought they were going 20% faster. Let me say that again. Coders thought AI was making them faster, but it was actually making them slower. The only reason the researchers know it slowed coders down is they screen-recorded all of the work and timed everything themselves.

The truth is, humans aren't very good at metacognition. We aren't very good at recognizing what we're good at and bad at. We aren't very good at judging our own productivity. We aren't very good at judging our own learning. It would be nice if we were, but we're not.

And when it comes to AI we are constantly being fed an enormous hype machine trying to convince us that AI is the future, that the clock is ticking on regular analog humans, that we need to hop on board or fall behind. That hype machine biases us to assume that AI is, in fact, intelligent, and that whatever it outputs must be better than what we would’ve produced ourselves.

This is just one study on coding. It doesn’t follow that using AI is always bad. I wrote a post a few months ago on using AI to generate word problems. I plan to continue doing that this school year. I use AI to translate when I’m communicating with families that don’t speak English. But that’s probably it. I’ve experimented with generating materials beyond word problems and I just don’t think it’s producing quality resources. If I give AI a quick prompt and use what pops out, it’s typically not very good. If I spend a while prompting again and again to get something better, I might as well write it myself.1 Everything else I’ve tried to use AI for follows the same pattern: it’s either bad, or too much work to make it good. Word problems are my one exception because they are so labor-intensive to write, and when I write word problems they’re often too repetitive. Make your own decisions. I’ll keep experimenting and I’m sure I’ll find some new uses as time goes on. But remember that it’s easy to fall for something new and shiny, and convince yourself that the newness and shininess means it must be better than what you did before.

My argument is that we should approach AI use with intense skepticism, and we should reserve extra intense skepticism for any suggestion that we should have students use AI. This post is a reminder of our biases, not an ironclad rule. If you head back to work and that eager colleague or consultant or whoever tells you about this amazing AI tool that you absolutely have to use, I hope you remember this little nugget and approach it with healthy skepticism.

Craig Barton has a nice post on creating resources with AI here. It’s worth reading if you want to give AI-created resources a lot. But Craig emphasizes that it often takes multiple rounds of prompts and edits before you get something useful, which maybe just reinforces my thesis. Still, Craig’s approach is the best I’ve seen and it’s worth checking out.

I ran into that paper recently! There are definitely A LOT of things to consider in regards to LLM AI in education. I'm just n=1, but here have been my experiences.

AI models continue to improve. My experiences last year may not be true now.

I appreciated that the linked study identified the different degrees ai was used in the programmers workflow. But *how* LLM is used matters. In programming it can be used to write code, or to reference documentation, or to organize the programmers thinking, etc etc. As far as I could tell the study reported the degree of AI use, but I didn't catch any *how*

I also used an LLM to help me write physics problems for a buoyancy unit. I noticed that the story problems lacked that scaffolding finesse that helps guide students into developing a deeper understanding of the underlying phenomenon. This is the "do it for me" type of task.

On the other hand it did feel useful to have a conversation with it when developing my unit. I just recently picked up physics, I am the only physics teacher in the school, and university was 20 years ago. I call this a "talk with an expert" mixed with "finding a solution" task. I didn't blindly follow the results, and was also referencing open stax textbooks.

Some, like diffit, are fantastic for very dedicated tasks, such as converting a text into multiple reading levels. The prompts it also generates are sometimes useful too, but I try to be consistent with my student response prompts and graphic organizers.

My metacognition is probably spoofing me on how well it helped my wire my unit. Yet I'm fairly firm in my conviction that a tool with a very specific function, like diffit, speed up my ability to adapt curriculum

Thanks for drawing attention to this study. Too many studies on use of AI rely on self-assessment of whether it helped.