You Should Use Mini Whiteboards

The best way to check for understanding

If there is one teaching tool I recommend, it’s mini whiteboards. Mini whiteboards are the best way to see what students understand and adjust my teaching on a minute-to-minute basis. That change didn’t happen overnight, though. It took me a few years of trial and error to get my system right. This is my guide to using mini whiteboards in math class.

The Basics

Here’s the basic idea. Every student has a mini whiteboard and a marker. You ask a question — maybe you write it on the board, or project it, or something else. Each student writes their answer on their mini whiteboard. Then, on my signal, students hold their whiteboards up facing me so I can see each answer.

This is the absolute best way to check for understanding. In very little time, I can sample the entire class and get a sense of what students know and don’t know. The activity is flexible: I can ask as many or as few questions as I want, I can adjust in response to student answers, and we can do a quick reteach and practice on the whiteboards if necessary.

One thing to emphasize right off the bat. I love mini whiteboards. You might assume I spend large chunks of time using them. I don’t. The majority of my class students are solving problems using pencil and paper, or we are talking about the math they’ve done on pencil and paper. In a typical class I will do two rounds of questions on mini whiteboards, each 1-5 questions long. Sometimes it’s more, sometimes it’s less. This isn’t the main way that students do math in my class. Mini whiteboards are a bit slow: I ask a question, then I wait until every student has a chance to answer, then students hold their boards up, then I take a moment to scan, and then we are on to the next question. Nothing wrong with going slow sometimes, but paper and pencil is much more efficient if I want to maximize the number of problems students solve. I pick a few well-chosen mini whiteboard questions to help me make decisions about what to do next, when to move on, and when to intervene. Then we put whiteboards away and get back to pencil and paper.

When to Use Them

Here are a bunch of places I use mini whiteboards in my class. I don’t do all of these in a single class, though over the course of a week I might use each of these at least once.

Prerequisite knowledge check. In every lesson, there is prerequisite knowledge that it’s helpful for students to know. If we’re graphing a proportional relationship, they should know how to plot points on a coordinate plane. If we’re solving two-step equations, they should know how to solve one-step equations. If we’re solving complementary angle problems, they should know that a right angle measures 90 degrees. Mini whiteboards are a great way to check these skills toward the beginning of the lesson. Pick a few prerequisite skills and see whether students have those skills down. If they’re shaky I give a quick reminder and we do some extra practice on mini whiteboards.

Check for understanding from a previous lesson. Do students remember what they learned yesterday? Sometimes yesterday’s lesson is a prerequisite skill, but other times it isn’t. Either way, it’s worth checking whether students remember yesterday’s lesson so I know if I need to revisit those concepts in the future. My experience is that students remember far less the day after a lesson than I would like. A quick check holds me accountable and points me to the skills we need to spend more time on.

Check for understanding before independent practice. Students are about to start some independent practice. Are they ready? Mini whiteboards are the best way to check. Ask a few questions similar to the independent practice questions and see how many students get them right. I have two possible follow-ups. If a large portion of the class gets it wrong, I need to stop and do a full-class reteach. If most students get it right, I can jot down the names of students who made mistakes on a post-it and check in with them individually as we start independent practice.

Check for understanding of atoms. This is really a topic for a longer post, but the short version: divide your objective into the smallest possible steps, and teach one step at a time. This often means you need to teach multiple “atoms” — small steps on the way to a larger objective. Mini whiteboards are a great way to check understanding of those atoms and make sure they are secure before jumping into a larger skill.

Stamp after a discussion. Let’s say I notice a common mistake. A bunch of students say that -4 + -5 = 9. (This is a common mistake after introducing multiplication with negatives, as students apply the rule for multiplication to addition.) So we discuss it as a class, visualize it on the number line, and talk about the difference between addition and multiplication. That discussion is nice, but it often doesn’t stick. After the discussion I have students grab mini whiteboards, and we do a few quick questions to stamp the learning.

Step-by-step. Let’s say we’re doing a multi-step problem. Mini whiteboards are a nice way to work through it step-by-step. Have students complete the first step, then hold up whiteboards and check. Then repeat for the next step. This is a great tool to figure out where in a complex procedure students start to get confused.

Check an explanation. Maybe we’re talking about something conceptually tricky, like why multiplying three negatives results in a negative but four negatives is positive. I can ask students to write their explanation on mini whiteboards: why does multiplying four negatives, like (-3)(-2)(-10)(-1), result in a positive? I can’t read a full class of explanations all at once, but I can read a bunch and get a sense of how well students understand that idea.

Give students a bit of quick practice. If I realize students just need a few more questions of practice with something, beyond what I have prepared for pencil and paper that day, mini whiteboards are always there. While I usually go one question at a time, I will also occasionally give students three to five questions, have them try all the questions, and check them all at once as best as I can. This isn’t quite as powerful as a check for understanding, but it’s an efficient way to get a few quick practice questions in.

Some Questions and Answers

That was the heart of the post. Mini whiteboards are great. They’re useful for all sorts of stuff in math class. You should use them.

If you want to hear more about all the nitty gritty details of how to set up a mini whiteboard system in class, read on. Credit to Adam Boxer here. His blog posts and webinars have been a huge help in refining my mini whiteboard systems. That said, there’s no magical advice to make mini whiteboards work perfectly. It takes time and lots of little adjustments. Read everything you can find, but if in doubt give them a shot, see what works, and refine from there.

Q: This sounds really cool. Mini whiteboards must have changed your classroom overnight!

A: Not exactly. Rewind: it’s a little over three years ago. I’m in my second year teaching 7th grade math. I’m following the curriculum, so on Monday I teach Unit 2 Lesson 3, on Tuesday I teach Unit 2 Lesson 4, and so on.

It isn’t going well. Lots of students aren’t learning. I’m trying lots of things, I’m making slow progress, but that progress sure feels slow. So I start using mini whiteboards. Toward the end of each lesson I have students pull out the mini whiteboards, and I ask some check for understanding questions. And every time, half or more of the class get them wrong. There wasn’t much time left in class. Now I know much of the class is confused. What am I going to do? I don’t have time to deal with all of that.

This felt really hard. And in the long term, this type of checking for understanding drove a ton of positive changes in my teaching. I wrote a bit about this in a previous post. I won’t get into all those little details now.

But that leads me to a piece of advice. In my experience, the best place to start with mini whiteboards is a prerequisite knowledge check toward the beginning of class. It can feel discouraging to ask questions, get a lot of wrong answers, and not have the time or the tools to address it. That’s also discouraging for students and can reduce motivation over time. Starting with a prerequisite knowledge check at the beginning of class can still be discouraging, but you have way more time to respond. Even a quick reminder and a round of practice with a prerequisite skill can make a difference in that lesson. Over time you can add more mini whiteboard tools to your toolkit, but this is a good place to start.

Q: That sounds cool. I have some boring logistical questions though. How do you make sure students don’t copy each other?

A: So here’s the routine: students write their answer to a question, then they “flip and hover”: they flip the whiteboard upside down and hold it hovering above the desk. This serves two purposes: one, it reduces cheating, and two, it signals for you which students are finished.

This doesn’t reduce copying to zero. You still need to be an active teacher, stand where you can see as many students as possible, and scan the room.

Q: What do you do if students just don’t answer and leave the whiteboard blank?

A: This is really tricky. Some teachers might recommend requiring students to write a question mark or something along those lines. I don’t want to get into power struggles with students over whether they write a question mark when they’re confused. Instead, here are a few steps I take when I see a student not answering:

I try to start each round of whiteboard questions with a very simple question I know everyone can answer. This gives me a barometer: if a student isn’t answering this question, they’re not paying attention or opting out. It’s really important not to mistake opting out and being confused. If a student just doesn’t know enough to attempt the problem, that’s good data for me!

Ok but some students are still opting out. I try a bunch of little nudges to get students participating. I seat students who are more likely to opt out toward the front. I use proximity and nonverbal cues to remind them. I try to keep the success rate high — if I ask too many hard questions, students get used to not knowing the answer and are more likely to opt out.

If those nudges don’t work and I’m confident the student is opting out rather than confused, I will either hold the student after class or have them come in for a few minutes at lunch. The logic is simple: you weren’t answering questions, so you must need some extra help. I try not to frame it punitively. If they do need extra help, then they get it! If they don’t, they generally don’t like this very much and will be more likely to participate. If all of that doesn’t work, I contact home.

In all of this I have to distinguish between students who are confused, and students who are opting out. If a student is confused, I offer them support and make sure it isn’t framed as a punishment. As long as they are trying the questions they know how to do, we’re fine. If a student is opting out, I focus on all these little nudges to try and get them participating.

This doesn’t always help for every single student. But I find that this works for the vast majority. If 1-3 students in a class participate inconsistently, it’s not the end of the world. I can work to improve their participation on an individual basis and avoid power struggles in the moment. But I need to be diligent with my nudges: if non-participation gets much higher than that, it becomes contagious and can make mini whiteboards an ineffective tool.

Q: What do you do if students are being mean to each other about wrong answers?

A: I don’t have any brilliant tricks here besides keeping a really close eye on this, in particular when you first introduce mini whiteboards. When I ask students to hold up their whiteboards I pay attention for anyone who is looking around the room at other students. Even a quick laugh at another student can shut them down for the class. The goal is to create a culture where mistakes are totally normal and we learn from them as a class, and to also catch any students who are mean right away and nip that in the bud.

Q: Tell me more about the routine and some of the details.

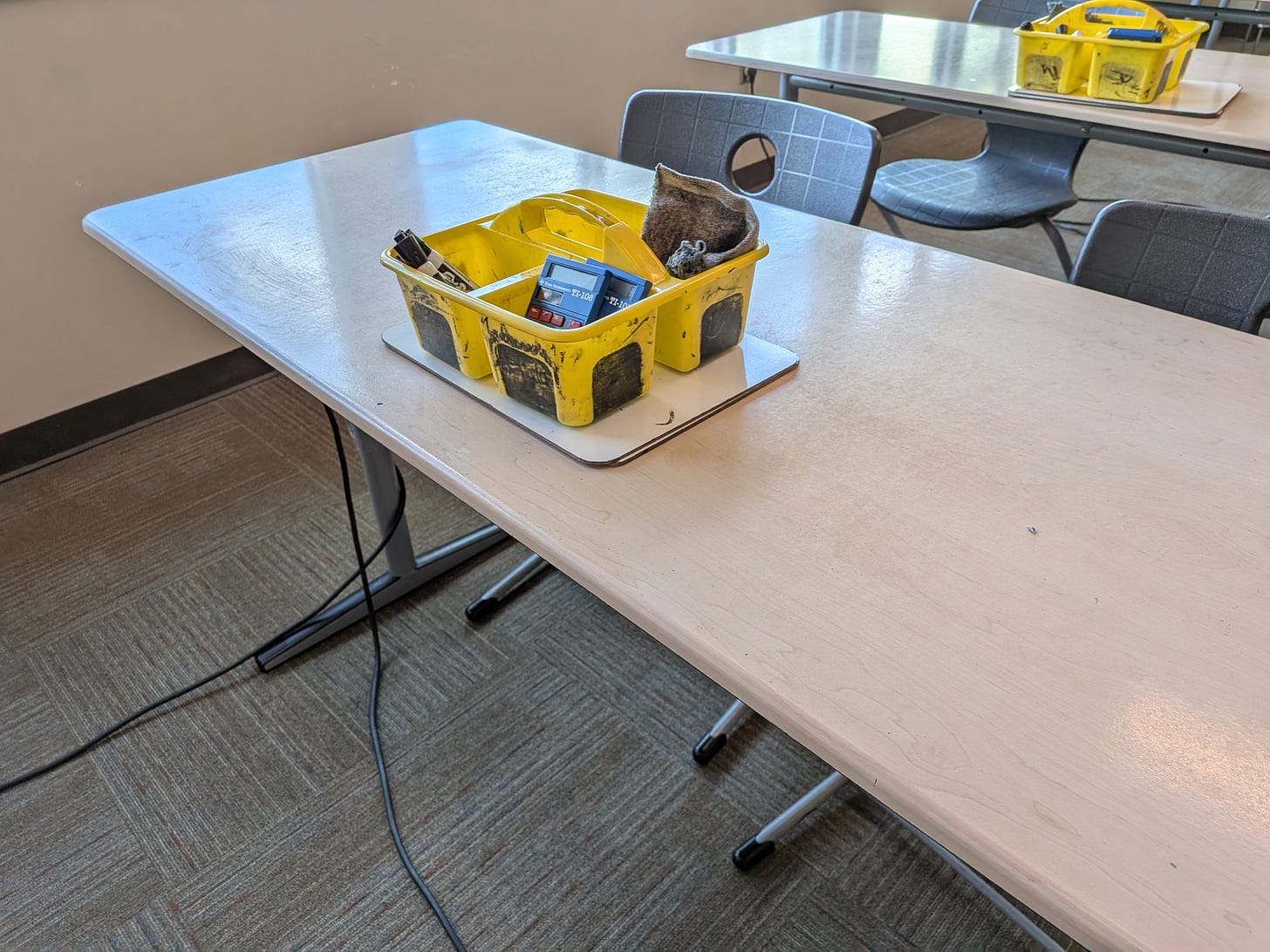

A: Here’s what my tables look like (two students per table).

In each bin are markers, cut-up towels for erasers, and calculators when necessary. Whiteboards are stacked underneath.

When we’re not using them, whiteboards stay stacked under the bin, and markers are off-limits. I try to be diligent about this. They are very fun toys if I’m not paying attention.

When we’re going to use them I ask students to grab a whiteboard and a marker, and to quickly test their marker. I observe to make sure students are grabbing their whiteboard and prompt any students who aren’t. I keep extra markers on my desk, and try to keep extras in bins. It only takes a few seconds for everyone to be ready to go and give out an extra marker or two where necessary. I mostly either write questions on the board or on a piece of paper under a document camera. Again, after asking a question I observe to make sure students are solving and writing their answers, and prompt students who need an extra nudge. I try to give plenty of think time. I remind students to flip their whiteboards upside down once they’ve written their answer. Then, once students have written their answers, I say, “whiteboards up, go.” On go, they hold their whiteboards up. I try to look at each whiteboard individually. This whole process takes time, which is why it isn’t ideal for extended chunks of class, but it makes up for the slower pace with the quality of information I’m getting.

I often ask questions addressing a few different goals in one session. For instance, in one round at the beginning of class, I might ask a question checking for understanding from yesterday’s lesson, two prerequisite knowledge checks for the current day’s lesson, and a follow-up for a common mistake from the Do Now. Then, if necessary, we spend a bit more time on any of those topics.

When we’re done, I say “erase, stack, markers back” (get it, it rhymes!) and students put everything back. I also actively observe here. It’s very tempting to keep the whiteboard out and draw something, or to use the marker to draw on your arm. They all have to go back before we move on. With time students get fast at this. The goal is to be around 15 seconds transitioning to or from whiteboards.

Q: Where do you get the whiteboards, markers, and erasers?

A: I found the whiteboards in my room when I started at this school. Any whiteboards will do, though I will say a regular piece of paper size works well, they don’t need to be much bigger than that. Two-sided whiteboards are nice because it’s very tempting to graffiti the back. We don’t do much graphing in 7th grade but if you teach older students there are two-sided mini whiteboards with a coordinate plane on one side. Erasers are just pieces of cut-up towel. Initially my school provided plenty of markers. The budget is a bit tighter now, and when they stopped providing markers I made a bit of a fuss. I said that science teachers get lab supplies, English teachers get books, and so on, and for me, the essential tool in my math class is mini whiteboard supplies. My principal agreed to spare a bit of money. I buy markers in bulk. I get by on <$100 of markers a year, and I bet you could get a set of whiteboards for your classroom for <$100. Your mileage will vary but I think that’s a perfectly reasonable ask for a typical school and you can often find some random underused department budget line to put it on. I recommend Expo for markers, the nice brand-name markers just last way longer than the cheap ones. I am also diligent about making the most of the markers I have. If a student says a marker is dead, I don’t just throw it out. I toss them in a pile on the windowsill. Sometimes it’s dead because a student didn’t put the cap on all the way, and giving it a rest with a cap on can bring it back to life. If the tip gets pushed in, I have a pair of needle-nose pliers to pull it back out.

Q: What do you do if students are drawing graffiti on the back, or drawing pictures of dogs instead of doing math?

A: I keep a close eye out and try to nip this in the bud early. A nice consequence here is inviting the student to come outside of class time and help clean the whiteboards or black out graffiti.

Q: Any final advice?

A: I just want to emphasize something I mentioned earlier. Mini whiteboards are great. You should use them. But this isn’t some magical teaching tool that will transform your classroom overnight. First, there are a lot of little logistical things you have to get right. You’ll learn quickly how to make sure whiteboards go away promptly, how important it is to have a high success rate so students don’t get discouraged, how to respond to students who are opting out. Second, you might get really discouraging results. I know I did. There are two main benefits of mini whiteboards. One is a check for understanding: did students understand what I just taught? Do students know what they need to know to access this lesson? That check for understanding is really valuable. The second benefit is that mini whiteboards give broader insight into whether my teaching is working. If, over and over again, students don’t remember what they were supposed to have learned, then something is wrong. It’s easy to blame the curriculum, or last year’s teachers, or the parents, or school culture, or whatever. I’ve been there. But I’ve found that there are lots of changes I can make to my teaching in that situation, and mini whiteboards serve as a rapid-fire barometer to figure out what works and what doesn’t. The second benefit has mattered more to me. It’s felt discouraging at times, and the progress is often slow, but mini whiteboards are a great way to see which changes in my teaching have helped students learn more math.

"Q: What do you do if students are being mean to each other about wrong answers?"

I had a coach suggest asking the class, "Why might an intelligent person answer...?" With that framing, it's a little safer to answer: even if the student is wrong, they just got called intelligent! And if they know that's not the right answer, they have to think about why the right answer is more accurate. Strategic cold calling is really useful here.

"Q: Where do you get the whiteboards, markers, and erasers?"

I bought some shower board from the Home Depot across the street from my school and asked them to cut it into 2 foot squares. The attendant hesitated until I said it was for school, and then he was all in. (In hindsight I should have gone smaller.) They don't last as long as the "professional" MWBs, but they're a whole lot cheaper to replace.