The Motivation Fractal

Success leads to motivation

Motivation is complex. There are a lot of possible reasons a student is motivated or unmotivated. If I want students to work hard in math class, I have to pull lots of levers. Curiosity, relevance, autonomy, belonging, relationships, and safety all matter.

One challenge is that motivation is deeply individual. Something that feels relevant to one student might not be relevant to another. The best motivation strategies are those that work for an entire class, so I'm not trying to juggle the motivational states of each student in the room.

In my experience, the best motivation strategy is simple. Humans like doing things we feel good at. I want students to feel successful in math class. If they feel successful, they are more likely to feel motivated and build positive learning habits.

Math teachers often complain that students aren't willing to try hard problems. They look at a problem, say "I don't know," and give up. There's no easy solution to this problem. The best answer I've found is to help students feel successful before trying a hard problem. Build up to it with a few easier, more accessible problems. Use success to build momentum. It doesn't work every time or for every student, but it helps.

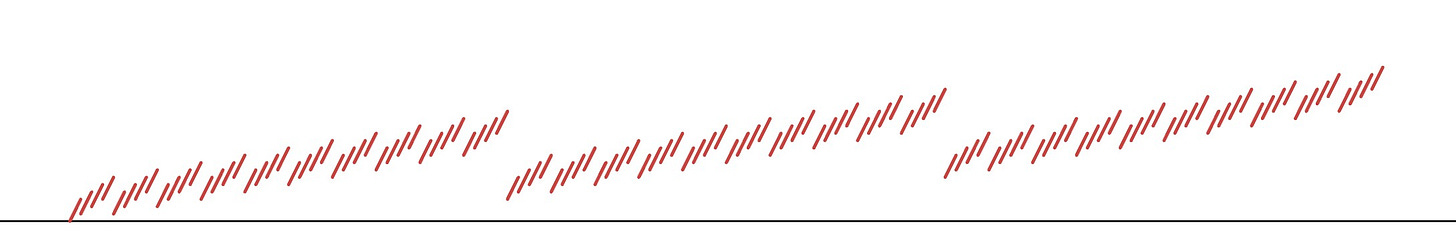

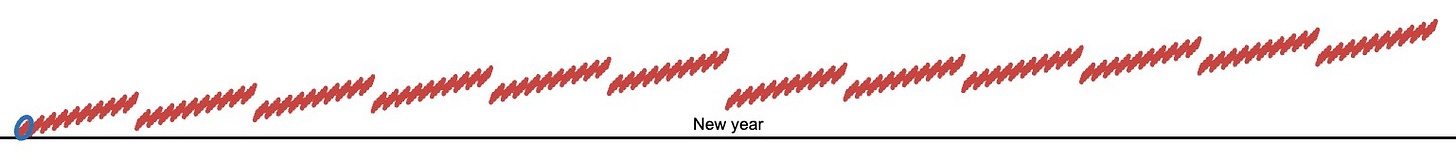

Here's a rough mental model for this idea. The motivation fractal:

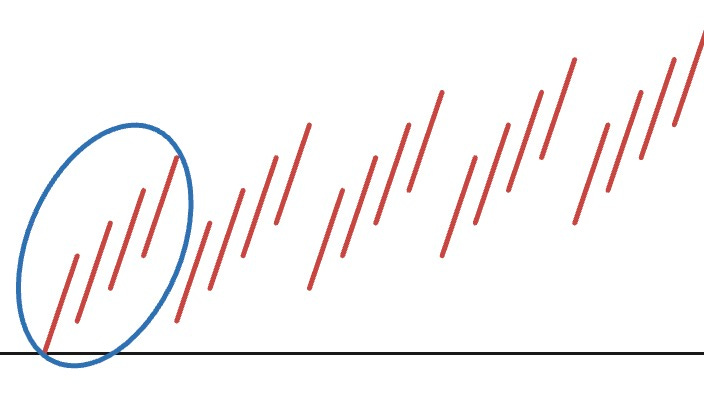

Time is on the x-axis, and difficulty is on the y-axis. Let’s zoom in.

A single class is circled. In each class there are a few activities — a warmup, introducing new content, practice, etc. Each activity is represented by a line segment. Within each activity, the difficulty gradually increases, starting easier and getting more difficult. Within one class, each activity gets a little bit tougher, though it still starts easier than the last one ended. The same for each class — it starts easier, much easier than where the last class ended, but gradually gets harder. Then the same again for a topic (or strand). You could zoom out more and say the same thing for each year of school.

This is only a mental model. All the logistics and practical realities of teaching mean I can't do exactly this every day. But I find the broad idea helpful. The motivation fractal is what I strive for. When I see motivation flagging, I try to build in a more gradual increase in difficulty in the activity, or class, or topic.

Motivation is complex. There's more to it than these images. But the motivation fractal is the most effective tool I have. A full class of students has all sorts of different needs. Students who don't speak much English. Students with IEPs. Students who feel bad at math. Students who are worried about all sorts of things outside of math class. They all have different interests and personalities, different levels of knowledge, different things that drive them. The strategy that is most effective for motivating all of them at once is the motivation fractal. It's not perfect, and it's not a magic bullet. But when I do a good job of starting small and gradually increasing the difficulty, building confidence as we go, I can see slow, steady progress in motivating my students.

It's not only students who are motivated by feeling successful, teachers and TAs are too [cross reference effective cpd!]

Sadly, the majority of leadership I see today, does the reverse!

This is why Saxon math textbooks were so good.