Some Strategies for Motivation

Nothing groundbreaking here, but a lot of little things that make a difference

The new school year is about to begin, and I'm planning for the first days of school. One thing I think a lot about in the opening days is how to maximize student motivation in math class. I want to do a deep dive into how I think about motivation in one specific context.

I often hear teachers talk about motivation as if it’s a static property of students. A given student is either motivated, or they’re not. I disagree. Motivation is slow to change, but it can change, and the beginning of the school year is the best time to help students become more motivated. That’s what this post is about.

Every day my class starts with a Do Now. You can read in detail about my routine here. Short version is, students pick up a half-sheet of paper with five blanks, there are five questions on the board, and students answer them.

At my current school, getting students to complete a Do Now isn't simple. I've worked at other schools where almost every student does similar tasks without thinking twice because that's part of the school culture. That's not the case where I work now. No use crying over spilt milk; many teachers reading this will recognize what I'm describing. If you don't use a Do Now or you have trouble motivating students in other parts of class, the same principles apply.

There's no one trick to motivate students to do something. There are a bunch of different strategies, and the more strategies I use, the more success I will have. The ideas in this post are drawn from "self-determination theory," which is a psychological theory about motivation. If you'd like to learn more about it, the Wikipedia page is a good place to start.

Self-determination theory posits a bunch of different factors that influence motivation. Here is how I use these ideas:

Competence

Humans like to do things we feel good at, and we don't like to do things we feel bad at. Humans also like to get better at things, and to see tangible evidence of that progress. This isn't easy. I have to teach my students 7th grade math, and they are coming in with a wide range of skills. When I write my Do Nows I start with simple questions. I reteach some foundational skills early in the year, then put those skills on Do Nows. I aim for 4 questions that the vast majority of students get right, and one tougher question. If a lot of students get a question wrong, I do a quick reteach and include a similar question the next day. If necessary I do this multiple times. The goal is for students to get questions right, and for students to see themselves learning new things and growing day by day. Competence is always important, but it can pay extra dividends at the beginning of each class to create momentum and motivate students to try harder tasks as class goes on.

Relatedness

Humans like to do things with other humans. Relatedness is the core of why learning in classrooms, despite the myriad differences of any group of students, makes sense: we are working together toward a common goal, and that togetherness helps to motivate students. The most important insight about relatedness is that one powerful factor in whether a student is motivated to do something is whether everyone else is doing it. If I can start the year strong with clear expectations and high participation, that participation becomes self-reinforcing. Many students, in the opening days of school, will often look around the room to see what everyone else is doing, and if they see a large majority putting in effort they likely will as well. This means I start my Do Now routine from day one, when students are able to build new habits and want to make a positive first impression. The second important element of relatedness is to never emphasize when a student or group of students isn't putting in effort. If I put the spotlight on students who aren't doing what I ask them to do, that broadcasts their behavior and undermines the collective feeling I want students to have. Of course there will be students who are recalcitrant at times. That's normal. But I can choose to handle those cases with care, and without drawing undue attention.

Autonomy

Humans like to have a feeling of freedom, to feel like they have choice in what they are doing. This is tricky in classrooms. There are lots of ways schools give students fake autonomy. "You can choose this problem, or that problem." Those types of choices don't generally make students feel like they have real autonomy. Letting students choose where they sit can lead to poor choices and negative peer effects. I am really cautious about autonomy in my room. But the flip side is that I don't ever want to use coercion. I avoid giving fake autonomy, and I'm probably not maximizing the motivational effects of autonomy — that's a reality of mass compulsory education. But there's a mistake teachers can make where a few students aren't doing something, and the teacher stands over them and tries to strongarm the student into doing the task. This is a bad idea. Even if it works in the short term, a power struggle eliminates any sense of autonomy for the student and is likely to undermine motivation in the long term.

Extrinsic motivators to avoid

Rewards and consequences are common tools in education. Maybe it's giving students candy, or holding a student for a few minutes of lunch, or promising students a party if they all meet a certain standard. The core insight about rewards and consequences like these is that they can undermine motivation in the long term, especially if they are overused or if they are used too much and then discontinued. I really try to avoid things like this. First, it's tons of work for me. Do I want students to do my Do Now? Yes. But it's just one of many elements of my class. I can't bribe or punish students for everything. I want students to do the Do Now because they build a habit of coming into class each day and answering a few questions, not so they will get a reward.

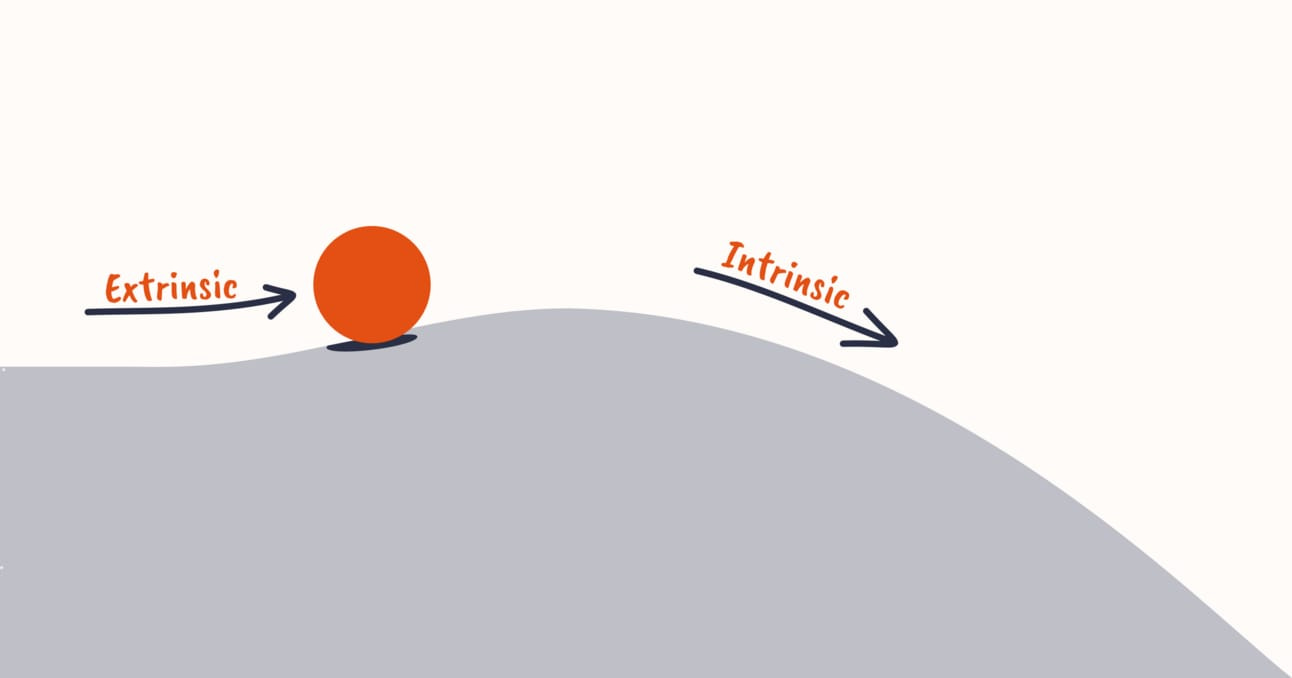

The trickiest form of extrinsic motivation is grades. I don't want to emphasize that students should do the Do Now for a grade. I don't have time to grade it every day, and that motivation will fade over time. But I also can't ignore grading entirely. I work in a school where students often internalize the message that if it's graded it's important, and if it's ungraded it's unimportant. I grade a Do Now about once a week for the first few weeks, and gradually scale back to about once a month as the year goes on. My goal is to send a message that this is important, but I also don't make a huge deal of the grades. Hopefully that extrinsic motivation helps students to build good habits early in the year, then fades into the background. Peps Mccrea calls this "motivational handover" and has this nice visual:

The goal isn’t to avoid rewards and punishments entirely. The goal is to use them judiciously early on, and let them fade into the background as the year progresses.

Useful extrinsic motivators

There are two kinds of rewards that can be really helpful, and don't incur some of the risks of other types of extrinsic motivators. The first is praise. Everyone loves to be praised. I try not to go too crazy with this, but I also want to give positive verbal feedback on a regular basis. I pay particular attention to students who are doing great work day in day out, and students who have improved — in particular students who were struggling with a certain type of question, and then get it right on a Do Now. The second is now-that rewards. Here's the idea. If-then rewards, where I tell students "if you do x, you will receive y reward," are a risky type of extrinsic motivation. They can lead to students focusing only on the reward, they lose power over time, and if I stop giving the reward they will cause a decrease in motivation. Now-that rewards are rewards given after a student does something well, recognizing great work without dangling incentives in front of students to get them to do something. Now-that rewards are great to give as shoutouts or recognitions at community meetings or other gatherings, and while they can seem small they are a much more powerful long-term motivator than many other little carrots and sticks. I learned about if-then vs now-that rewards from this blog post by Adam Boxer.

Types of extrinsic motivation

The final insight from self-determination theory is that there are different types of extrinsic motivation. The most shallow and fragile is doing something to get a reward or avoid a punishment. That might work in the short term, but isn't likely to last. On the other side of the spectrum is doing something because you value the goal and see the effort as an important part of reaching the goal, or because you see that type of effort as part of who you are. These are still extrinsic motivation — students might not answer math problems because they are inherently enjoyable — but this is a much more durable and long-lasting form of extrinsic motivation. I use this language in how I frame for students why the Do Now is important, why practice matters, and why math is worth learning. I want students to say to themselves, "ok let's get to work, I want to learn math and this is what I need to do to learn."

Relationships and student interests

The two most common motivation strategies I see teachers talk about are building relationships with students and framing learning around student interests. I'm not opposed to these. I work hard to build relationships with students, and when possible I do my best to incorporate student interests into math class. But they aren't my first motivation strategies. I have too many students, and if I only use relationships and student interests many students will fall through the cracks, and won't build positive habits early in the year. I think of these as my backup strategies. If I do a good job with everything I listed above, I can get most of my class motivated to work hard on a regular basis. They won't work for everyone. Those whole-group strategies then leave me time to focus on the few students who I haven't been successful with. Then, I might focus on building relationships, learning about their interests, or finding other strategies tailored to the individual students. But the important part is that I focus on whole-group motivation strategies that work for the majority first.

Closing

I used the Do Now as an example in this post, but all of these strategies can apply to any other part of class. I focus first on everyday routines because that’s where students develop habits they repeat each day. The same strategies apply to all of math class, or any other class.

The toughest part about these strategies is they can be slow to work. They won’t transform students overnight. But gradually, over time, they make an enduring difference. It might be tempting to bribe students with candy to get some short-term wins, but they’re unlikely to last. A deep understanding of motivation is what makes a gradual but lasting difference.